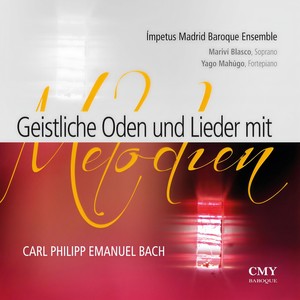

C.P.E. Bach: Geistliche Oden Und Lieder Mit Melodien

- 演奏: Yago Mahugo

- 歌唱: Marivi Blasco

- 乐团: Impetus Madrid Baroque Ensemble

- 发行时间:2014-12-31

- 类型:录音室专辑

- 歌曲

- 时长

-

作曲家:Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach( 卡尔·菲利普·埃马努埃尔·巴赫)

-

作品集:Gellerts Lieder, Wq. 194/9

-

作品集:Gellerts Lieder, Wq. 194/7

-

作品集:Gellerts Lieder, Wq. 194/15

-

作品集:Gellerts Lieder, Wq. 194/30

-

作品集:Gellerts Lieder, Wq. 194/46

-

作品集:Gellerts Lieder, Wq. 194/49

-

作品集:Sturms Lieder, Wq. 197/2

-

作品集:Sturms Lieder, Wq. 197/11

-

作品集:Sturms Lieder, Wq. 197/13

-

作品集:Sturms Lieder, Wq. 197/29

-

作品集:Sturms Lieder, Wq. 198/2

-

作品集:Sturms Lieder, Wq. 198/7

-

作品集:Sturms Lieder, Wq. 198/29

-

作品集:Gellerts Lieder, Wq. 194/7

-

作品集:Gellerts Lieder, Wq. 194/9

-

作品集:Gellerts Lieder, Wq. 194/15

-

作品集:Gellerts Lieder, Wq. 194/30

-

作品集:Gellerts Lieder, Wq. 194/46

-

作品集:Gellerts Lieder, Wq. 194/49

-

作品集:Sturms Lieder, Wq. 197/2

-

作品集:Sturms Lieder, Wq. 197/11

-

作品集:Sturms Lieder, Wq. 197/13

-

作品集:Sturms Lieder, Wq. 197/29

-

作品集:Sturms Lieder, Wq. 198/2

-

作品集:Sturms Lieder, Wq. 198/7

-

作品集:Sturms Lieder, Wq. 198/29

简介

CARL PHILIPP, LIEDER COMPOSER We must assert, with the French musicologist Marcel Beaufils, who wrote a great deal on the topic, that the word lied does not really mean anything. It would seem to be related to lai, itself derived from the Welsh, Cornish and Breton lay. It would by then already be an evolved form, a “musical poem”, as Paul Zumthor puts it in his Histoire littéraire de la France médiévale, or, in Paul Tuffrau’s eyes, a “prose narrative interspersed with songs”. By the 12th century it has lost any resemblance to the Celtic lai. In Germany, we find the form leich, a sort of dance-song which, with the Minnesänger, will develop into a cultivated, non-strophic form often used to praise the Virgin: a kind of madrigal. Throughout Germanic history, other terms connected phonetically and semantically to lay or lai had arisen: liet, leod, lieth... Or hluti, that is... sound. None of this sheds much light on the matter. Some time would pass before Zamacois coined this, modern, definition of lied: “original song, written to be sung by one person, composed with artistic ambition, but in an intimate style, devoid of vocal excess, and in which poetry and music fuse totally, the latter serving the former, and not the other way round.” This description would undoubtedly apply to many works penned by composers before Schubert, who followed, at a distance, not the far-off Celtic forms but those intermediate ones which marked the evolution and crystallisation of the genre, naturally taking in mediaeval popular songs, the enormous range of so-called Volkslieder on themes of terror or the phantasmagorical, decidedly mythical in nature, patiently collected over decades by Herder, first, then Arnim and Brentano. These collections of popular themes and songs would be used by later composers, Mahler foremost amongst them in the late 19th century. The song of the simple man is recorded and collected and, curiously, finds its way into the religious realm: there we find the sacred lieder of Wolfgang Franck or the semi-profane songs of Adam Krieger in the late 17th century. And the songs of Johann Sebastian Bach, so little known today. Throughout this period a somewhat byzantine discussion takes place regarding the spirituality of song, its moral purpose and, simultaneously, the requirement that it should spring from reason. Musicians and scholars, leading exponents of culture and the art of music of the Germany of the day, such as Matthisson, Marpurg, Scheibe and Mizler, rack their brains in search of a clear definition for these concepts which will, in any case, from the early 18th century onwards bear the mark of a host of poets such as Günther, Hagedorn, Uz, Gleim, Gellert, Kleist, Klopstock or Burger. At the end of this sequence, the peerless figure of Goethe. These cultural movements, linked in turn to social, political, religious or historical upheavals – such as, for example, the aftermath of the Thirty Years’ War – lead to a state of affairs conducive to the appearance of works for solo voice, which poetry, both learned and popular, can penetrate and thrive in; and which will fully blossom with Schubert. Some, like Oscar Bie, claim that lied before Schubert could be “contained, in its entirety, in a small, grey sack”. This is slightly exaggerated. Beaufils, once again, provides facts: Friedländer and Lindner count around eight hundred notebooks between 1689 and 1799 – Schubert had just been born – without taking into account works already published by Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. Amongst these compositions, there is a wealth of odes and spiritual songs, cultivated by the likes of Krause, André, Hiller, Schulz, Kirnberger, Agricola, Gluck, Reichardt or our present subject, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach. The undulation of the melodic line that Mozart would take to its apogee in parts of The Magic Flute can already be glimpsed in some instances, only here with a somewhat diluted Germanic flavour, slighter and less severe, more simple or volkstümlich. A route that Gluck would follow, in his manner, in his collection of seven odes by Klopstock, certainly commendable but a far cry from the expressivity and dramatic value he was able to concentrate in his operas. Pieces by another composer travelling the same path, Zelter, are of the volkstümlich type. There is significant evolution in the keyboard since Bach’s distant pieces, where the voice was accompanied by a sometimes workaday continuo, a structure which held sway throughout the first half of the 17th century, well-served by Bach himself, Handel and Alessandro Scarlatti. These scores, of varied stylistic quality, show major advances when compared with those of more middle-of-the-road authors. Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach’s remarkable production continues this path. Compositional style Every new exploration we undertake of Carl Philipp Emanuel’s scores leads us to admire once again their excellent craftsmanship, originality and stimulating development, forever forward-looking, pushing beyond the achievements of his great father, whom he and his brothers considered a fuddy-duddy... This praise can also be applied to his vocal works with harpsichord accompaniment, of which this CD presents a good selection.They belong to two collections: one holding 54 poems by Christian Fürchtegott Gellert (Wq 194), published by Winter in Berlin in 1758 and reprinted three times in the following years (the last by Breitkopf in Leipzig in 1784) and the other 60 texts by Christoph Christian Sturm (Wq 197 and 198), published by Herold in Hamburg in 1781 and 1782, making between them for a substantial part of the over 180 lieder he composed. Carl Philipp Emanuel’s style in this genre, ill-defined in his early Leipzig or Frankfurt compositions, becomes full-bodied and original in these Berlin ones, setting the tone for his later works in this field. One first notices in his mature songs and lieder the balance between the overly ornate and the overly simple. He favours the strophic form and the left hand usually doubles the vocal line in the keyboard part, which is fully written out. He does not shy away from using brief instrumental ritornelli, despite occasional interruptions to the flow of the vocal part. The poems by Gellert – who in his day became as influential as Heine would be later on – were full of substance and proved an inspiration to the composer, who respected indications regarding which verses might be sung as chorales. But the poet was well aware of the relevance of music, when he stated that “the best of songs without its own melody is like a loving heart pining for its spouse”. And for him, Emanuel Bach’s work was fundamental. He was genuinely impressed. The rigour of these compositions is clearly manifested in these words by the musician himself, contained in the preface to the publication: “In the preparation of the melodies I have, so far as possible, considered the entire lied. I say so far as possible because no-one who understands music can be unaware that one must not require too much of a melody to which more than one strophe is sung”. Although, as Geiringer points out, Carl Philipp was not fond of altering the music to match changes in the text, a relatively common strategy, as this would have barred his odes from being performed in religious services. This did not, however, make for completely rigid compositional planning. Indeed, as time passed, the composer moved away from a systematic respect of symmetry, such as occurs to a certain degree in Bitten, Wq 194/9, which became quite celebrated in the 18th century and which poses few problems for the singer given its highly regular construction. Although in general, the other pieces in the collection are more demanding, more so than songs by his Berlin colleagues of the day, like Krause. The vocal line in Bach is more difficult because it sometimes takes on an almost instrumental character. As happens, for example, in Passionslied, Wq 194/23, not the one from Book 1 of the songs after Sturm on the CD but another (he in fact wrote several with the same title). Darrell M. Berg highlights the prominent role of the keyboard in some of the lieder. We have a clear example in Wider den Übermut, Wq 194/49, whose introductions and interludes provide not only ornament but a harmonic rationale for the vocal line. And in Trost der Erlösung, Wq 194/30, the keyboard part forms independent counterpoint to the vocal line, when not mimicking it, and vice versa. The Sturm collection The history of Carl Philipp’s settings of Gellert – an author who, we should mention in passing, provided Beethoven with texts for one of his best-known collections – is well-documented; like that of other publications of vocal works, such as those written on psalms by Cramer. This is not so, however, with the two books of Sturm’s Geistliche Gesänge. The publisher was Johann Heinrich Herold. The theologian Sturm conceived his poems as being sung to chorale melodies, something that could be seen as a restrictive starting point. Bach most likely began composition of these lieder towards the end of 1779. Reactions on publication were extremely positive. And they gave the texts new life, leading to settings by other composers, albeit generally for mixed choir. It must be stressed that, as will be evident from listening to them, the lieder included on the CD are conceived as a “language of the heart”, speaking “straight to the heart”, as desired and expressed by the author, an approach which brings Beethoven to mind and which Johann Sebastian’s second son put into practice by seeking out poets like Gellert and Sturm; or for other songs, Lessing, Klopstock, Voss, Wieland or Miller. Cantagrel singles out amongst them Hölty, who would later be set by Schubert. In most of the songs performed by Mariví Blasco one can also detect the almost obsessive search for a solution lying halfway between recitative and the great arc of the aria, seeking perfection, and sometimes concentration, of expression. Just as his father before him, Carl Philipp writes out the ornaments in full, to defend himself from amateurs. And he is one of the first composers to head each piece with precise indications in the vernacular regarding the character to be given in performance: langsam, etwas langsam, mittelmäßig, lebhaft, munter, mit Affekt, gelassen, traurig… These songs are loaded with nuance, wrapped in a delicate harmony. Clear, limpid, simple even, but lithe and expressive, it does not conceal modulation and sometimes finds sombre tones or unexpected chiaroscuro effects, such as we may see in the song of penance, Bußlied, or its companion Prüfung am Abend, in a tortuous B minor, or, amongst the Gellert lieder, in Bitten, in a solemn E minor. Curious, expressive ritardandi, heighten the tension sought in songs like the unexpectedly chromatic Bußlied mentioned above. We should also mention, in the Sturm lieder, the rejection of tonality in some instances, such as Jesus in Gethsemane, which can translate into an almost painful expression. We are also struck by the durchkomponiert – through-composed – construction of Über die Finsternis kurz vor dem Tode Jesu. Over thirty bars, Cantagrel notes, he juxtaposes a seamless series of episodes and tonalities which culminates in the triple supplication of a German Kyrie. Carl Philipp Emanuel was taken as a model by Johann Abraham Peter Schulz, who in the preface to the edition of his Lieder im Volkston, declared that his aim was to “make good poems known to the public. The music will make it easier to remember them, will make them penetrate straight to the hearts, will drive people to hear them more often, and thus, adding to their charm that of a beautiful melody, will go towards making life a feast for the heart and the senses”, words we might apply to the work of Bach himself. If this message is to reach, and touch, the listener, performance of these lieder should be entrusted to a clear, high voice, a soprano or tenor, given the relatively high tessitura. The former would seem to be best suited to communicating what Carl Philipp had in mind; he did not, as will be seen, forgo ornament, sometimes profuse, in many of the pieces, which feature frequent appoggiaturas, acciaccaturas, mordents and other embellishments, the aim always being to make performance light and moving, unfettered and free. As free and winged as the keyboard part. This recording, following the composer’s own suggestion, includes some versions for solo fortepiano. Indeed, Bach stated in his preface to the Gellert collection, that he wrote with the keyboard player in mind, and his songs could therefore be performed without a singer, as pieces for solo harpsichord or fortepiano. Arturo Reverter translated by Aaron Vincent