- 歌曲

- 时长

简介

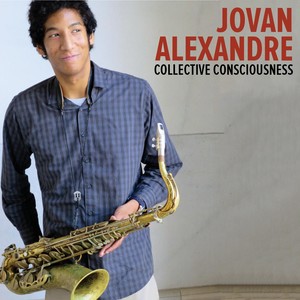

JOVAN ALEXANDRE Jovan Alexandre is an emerging jazz tenor saxophone phenomenon, known for the brightness of his tone and the elegant bearing of his compositions, who may be situated, broadly speaking, within the penumbra of a hard-bop style made popular in Alexandre's native Connecticut by the alto saxophonist Jackie McLean [1931-2006] in his later years. Alexandre has been a soloist on recordings for drummers Ralph Peterson (Outer Reaches [2010]) and Winard Harper (Coexist, sharing the tenor spotlight with Frank Wess [2012]), and for the South African jazz singer Nonhlanhla Kheswa (Meadowlands, Stolen Jazz [2013]). Alexandre's first album as a leader, Collective Consciousness, will be released worldwide on January 5, 2015 [on Xippi Phonorecords, XP22540]. Just as Jackie McLean himself had – in such albums for Blue Note as Let Freedom Ring [1962] and One Step Beyond [1963] – extrapolated upon both the lyricism and projection of a Charlie Parker or a Dexter Gordon and the angular modes and scales of John Coltrane, so has Jovan Alexandre positioned himself as a spiritual heir to McLean with authoritative and imaginative excursions into the free-flowing modernist colloquy pioneered by McLean. Alexandre's talented ensemble mates – guitarist Andrew Renfroe, pianist Taber Gable, bassist Matt Dwonszyk, and drummer Jonathan Barber – are similarly attuned to the aesthetic of controlled passion that Alexandre has inherited from McLean, so there is a certain hard-bop (and modernist) classicism at work in Collective Consciousness. Alexandre's uniqueness, though, and his album's, lies in his personal sound. He plays free of bombast, full of texture. His sound can variously seem molten and sharp-cornered within the same tune, sometimes practically within the same phrase. The melody lines are stately, whatever their tempo. Yet an understated, almost implied, restlessness inheres in nearly all his solos on Collective Consciousness. In Yalesville or in Irving Berlin's They Say It's Wonderful, the softly fitful tinges are framed in the manner of a Coltrane ballad such as After the Rain or Central Park West. Elsewhere, in Red Blues, To Music, or the title tune, Alexandre’s magnetic disquietude sources its power in quite different tempos, and he converts understatement to a bolder language. Alexandre says that some of the tunes on Collective Consciousness, such as the title tune and To Music, came together, as he wrote them, “like a puzzle. I probably wrote the form, chords, and hits before the melody, with the ending taking shape before the beginning, and I figured out what the final order should be later.” To Music, written by Alexandre at age nineteen [in 2008], uses improvised sections alongside composed melody and in-betweeen solos, “with a written line that cues back into a collective melody that acts as a send-off to the next soloist,” as Alexandre describes it. He says the harmonic movement in the piece is inspired by “composers like Joe Henderson and Jackie McLean,” noting that “the way the chords cycle and turn back to the top of the form is similar to the arrangement of Kenny Drew's A Callin' on McLean's album Rites of Passage [1991].” Stars in the Sky is in E major, “a difficult key for saxophone,” says Alexandre, “but practical because the lowest note on tenor, G# concert, is the major third, and the top note on tenor is D#, so we have the third and the seventh. For this tune, I did write the melody at the same time as the chords and the bass line.” Yalesville is in B major, a perfect fifth from Stars in the Sky, and another difficult key for saxophone. It has a very short eight-bar form that repeats. Alexandre explains that “the title is a tribute to my hometown. Yalesville is a village within the quiet Connecticut town of Wallingford, named after Charles Yale who purchased a seventeenth-century mill there in 1804. My family and I have lived there my whole life.” The Formula (for Kahlil Bell) “departs from the overall swing of the rest of the album,” Alexandre forewarns. “The drum beat and the melodic form are inspired by another of my mentors and collaborators, the drummer and percussionist Kahlil Bell, born in Harlem, raised in The Bronx, now living in East Orange, New Jersey. I admire the space he creates in his music. For instance, there may be sixteen bars of vamp on one chord, sixteen bars of melody, back to vamp for sixteen, then melody and solos or a bridge and send-off to solos.” Alexandre calls 25.1 “a reprise of the straight-ahead swing sound of the rest of the record. It's in Bb major, but moves around harmonically quite a bit. The bridge goes to E major sharp 11 which is a tritone away from Bb major. The title has a few different meanings to me. Firstly, it signifies my age when I wrote it (twenty-five [in 2013]). Secondly, the numbers 2, 5, 1 signify a workhorse harmonic progression to jazz players – sometimes written as ii-V-I. And lastly, 25.1 is numerically close to 26-2, the title of a composition I love on Trane's Coltrane's Sound album. To go along with that, the first four bars of 25.1 use the same progression as 26-2.” Alexandre conceived Red Blues as a salute, he says, to “all of the great musicians coming out of my alma mater, the Hartt School of Music, especially pianist Alan Jay Palmer and trumpeter Raymond Williams. After the melody statement, the solos are an A minor blues. When I listen to this song, the color red comes to mind, perhaps because red is our school color. And in naming the song, the overall energy of our playing, contrasting with the song's ‘blue’ minor key, struck me as interesting and, almost in some synesthetic way, as ‘red against blue.’ A unique feature here is that there is a cued interlude setting up a rhythmic break that lets the soloist create a new tempo. And on this song everyone gets a chance to solo.” Reconnaissance takes its name, Alexandre reveals, “from one of the possible meanings of the word – exploration. After the introduction to this song, we go into blowing with just horn, bass, and drums. We go exploring. I also found out later that a possible French meaning of the word, in English, would be gratitude. There is a written melody that I play on the last A part of the song form. Dyed-in-the-wool jazz fans may recognize the chord changes from Ray Noble's Cherokee. The solos are tenor, guitar, drums, and tenor again for the melody out.” Alexandre’s Wallingford is fifteen miles due north of New Haven. Several times a week during his high school years, he made the further trek northward to Hartford, a city rich in jazz history, to study at the Artists Collective, a neighborhood institution founded to promote the art and culture of the African diaspora and much beloved of Hartford’s African-American and Caribbean communities. The Artists Collective was founded by Jackie McLean with his wife Dollie McLean, transplanted New Yorkers, at a time of cultural and political ferment. The ensuing forty-five years have seen the Artists Collective evolve from humble physical beginnings in borrowed premises to become one of the nation’s most impactful grassroots teaching institutions in music – especially jazz – and other performing arts. In the 1980's, the University of Hartford’s Hartt School, a nationally prestigious conservatory, asked Jackie McLean to establish a jazz performance department. Alexandre is one of dozens of alumni of the Artists Collective to have continued their studies at Hartt. He graduated with distinction [in 2011] from the jazz program, now formally known as the Jackie McLean Institute of Jazz. At Hartt, Alexandre’s primary mentor was Jackie McLean’s own son, tenor saxophonist René McLean. He also studied with other direct protégés of Jackie McLean, especially tenor saxophonist Jimmy Greene and alto saxophonist Kris Allen, along with pianist and arranger Chris Casey, trombonist Steve Davis, and bassist Nat Reeves. These instrumentalists are all key contributors to what some have called a “Hartford sound” grounded in Jackie McLean’s teachings and continuing influence, and especially his notions of historicity and the value of hand-to-hand transmission of jazz knowledge. Even before graduating from Hartt, Alexandre had begun to earn a reputation as one of the most interesting of the new tenor saxophone soloists, through appearances with several top-name musicians such as Hank Jones, Dionne Warwick, Curtis Fuller, Harold Mabern, Larry Willis, Charles Tolliver, Randy Brecker, Antoine Roney, Benito Gonzalez, Shimrit Shoshan, and Kendrick Oliver & The New Life Jazz Orchestra. Alexandre and his current group have honed their work as a unit in regular appearances in all the principal jazz venues in Connecticut, notably New Haven's The 9th Note, Cafe 9, and the Owl Shop, and Hartford's Black-Eyed Sally's, the Bushnell Park Pump House Gallery, and the Charter Oak Cultural Center, and in those two cities' summer jazz festivals. They have also become habitués of the New York City jam sessions at Smalls, Fat Cat, Dizzy's, Minton's, and other new Harlem and Brooklyn venues. With the release of his debut album Collective Consciousness, an inevitable migration southward to New York City for more regular appearances there, and national and international touring on the horizon, Alexandre is poised for wider recognition as leader of his own ensembles, as a featured soloist, and as a composer of polished skill and high invention.