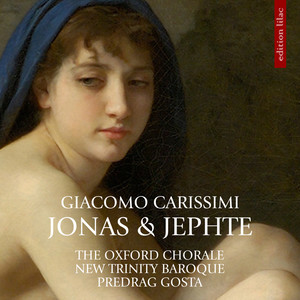

Carissimi: Jonas & Jephte

- 流派:Classical 古典

- 语种:英语

- 发行时间:2007-01-01

- 唱片公司:Edition Lilac

- 类型:录音室专辑

- 歌曲

- 时长

简介

Contemporary audiences know the term oratorio primarily through their experience of the works of composers such as George Frederic Handel, Joseph Haydn, and Felix Mendelssohn. The oratorio, however, was invented in Italy long before Handel’s time and was first developed as a musical entertainment for the presentation of Roman Catholic doctrine. Handel knew and was much influenced by the oratorios of his Italian predecessor Giacomo Carissimi, who is justly recognized today as the composer who established the oratorio genre. An oratorio is a non-liturgical, dramatic composition based on a sacred text, usually with a biblical subject. Carissimi’s oratorios were written for soloists, chorus, and orchestra, and told the story in recitatives, ariosos, arias, ensembles, and choruses. Unlike operas, his oratorios did not typically include scenery, costumes, or stage action. They often featured a part for a narrator, called a storicus or testo, and they assigned to the chorus a very important role as commentator on the action of the story or even, at times, as protagonist. While the oratorio was an invention of composers who worked in the early Baroque era, its origins may be traced to ideas and practices of the late Renaissance. The idea of the oratorio was born in Rome during the Counter-Reformation of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. In response to edicts of the Council of Trent (1545-1563), St. Philip Neri (1515-1595) began informal meetings with lay persons beginning in the 1550s in Rome. These meetings, which featured prayer, discussion of the scriptures, and the singing of sacred songs called laude, were designed to teach sound doctrine which the Church believed would encourage Catholics to remain faithful and also help to bring Protestants back to the Church. Philip’s “spiritual exercises,” as he called them, were held in prayer halls known as oratories. The Church encouraged the performance of excellent sacred music in the oratories in order to attract people to the prayer meetings and their accompanying religious instruction. In 1600, Emilio da’ Cavalieri composed a large-scale dramatic work for soloists, chorus, and orchestra on an Italian text for the Oratorio della Vallicella in Rome. This morality play, La rappresentazione di Anima et Corpo (The Play of the Soul and the Body,) is often cited by scholars as a forerunner of the oratorio. Other precursors were the dialogues published in the Teatro armonico spirituale in Rome in 1619 by Giovanni Francesco Anerio, which included examples such as La conversione di San Paolo (The Conversion of St. Paul.) By the 1630s and 1640s sacred musical dramas were being performed in Rome. Many were composed by Giacomo Carissimi, who was born in Marino, a town near Rome, in 1605. From 1623 through 1629, Carissimi was a singer in the choir, and then the organist for the Cathedral of Tivoli. He was named maestro di cappella at the Cathedral of Assisi in 1628, but he left this post in 1629 to become maestro di musica at the Collegio Germanico e Hungarico in Rome, where he worked until his death in 1674, and where many of his sacred dramas, later to be known as oratorios, were performed. Although Carissimi is known today primarily for his oratorios on Latin texts, he also composed Masses, motets, sacred concertos, and secular cantatas. He was so esteemed in his lifetime and afterward, that many compositions were falsely attributed to him. It is not possible to date Carissimi’s oratorios with any degree of certainty. As far as we know, there are no extant autograph manuscripts. Carissimi’s music is preserved in manuscript copies made by his students and others. Recorded for the first time on this compact disk are two arias and a duet for Jonas located in a manuscript now in Kromeriz, Poland. We know that Carissimi’s most famous oratorio, Jephte, was composed shortly before 1650, because Athanasius Kircher mentioned it in his Musurgia universalis published in Rome in 1650. Kircher also reproduced the music for the final chorus of Jephte, “Plorate filii Israel,” which he cited as an example of excellent rhetorical style. We admire Carissimi’s oratorios today for the variety of their recitatives, arias, ensembles, and choruses, and for their sensitive and dramatic text settings which continue to move our emotions. Carissimi’s oratorios were performed during the penitential season of Lent, and thus many of them feature themes of sacrifice, suffering, and redemption. The texts paraphrase and elaborate on scripture rather than quoting it precisely, a characteristic found in Jonas and Jepthte. Jonas (Jonah) is based on a story from the Book of Jonah, chapters 1-3, in which God calls Jonah to preach to the people of Nineveh. Jonah refuses and tries to flee the presence of God by taking ship for Tarshish. God sends a violent storm, and the sailors cast Jonah into the sea in order to make the storm subside. A great fish swallows Jonah and, after three days and nights, deposits him near Nineveh. There he repents and completes his prophetic mission. This story provides ample opportunity for dramatic moments. Cori spezzati are used to depict the great storm at sea in “Et praeliabantur venti” (And the winds battled) and the calming of the sea in “Tulerunt nautae Jonam” (They threw Jonah into the sea.”) The concluding chorus “Peccavimus Domine” (“We have sinned, O Lord,”) serves as a closing meditation. It features eight vocal parts moving in a rich polyphonic texture reminiscent of the late Renaissance style of Palestrina, with whose works Carissimi was familiar. The story of Jephte (Jephthah) is taken from the Book of Judges Chapter 11, verses 28-31. The Israelite general, Jephthah, about to go into battle with the Ammonites, vows to God that, if he is given the victory, he will sacrifice the first living thing to come out of his house when he returns home. This sacrifice turns out to be his only child, a young daughter. Jephte contains some of Carissimi’s most beautiful and profound music, especially the arias of Jephthah, the lament of his daughter, “Plorate colles” (“Weep, ye hills,”) an echo aria, and the final chorus for the people of Israel, “Plorate filii Israel” (“Weep, children of Israel.”) The audience of Carissimi’s day would certainly have been aware of the parallel between the story of the sacrifice of Jephthah’s child and the Passion of Christ which would be celebrated at the close of the Lenten season. This connection may be one explanation for the intellectual depth of the music in Jephte. As maestro di musica of the Jesuit College in Rome, Carissimi taught many talented young musicians including Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Johann Kaspar Kerll, and Christoph Bernhard. Through these pupils and others, Carissimi’s style was disseminated throughout Europe. As Winton Dean pointed out in his book, Handel’s Dramatic Oratorios and Masques (London, 1959,) Handel was greatly influenced by Carissimi’s work and borrowed from it freely. One example is the chorus “Hear, Jacob’s God” from Handel’s Samson which is modeled on Carissimi’s “Plorate filii Israel” from Jephte. Carissimi’s exquisite music still speaks to us across the centuries, expressing those deepest of human feelings which are our common heritage.