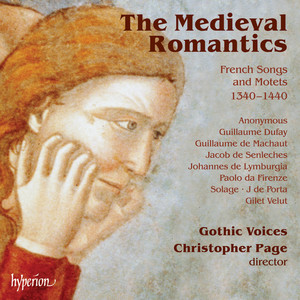

The Medieval Romantics: French Songs & Motets, 1340-1440

- 指挥: Christopher Page

- 乐团: Gothic Voices

- 发行时间:1991-10-01

- 唱片公司:Hyperion

- 类型:录音室专辑

- 歌曲

- 时长

-

作曲家:Anonymous

-

作品集:Anonymous

-

作曲家:Solage

-

作品集:Solage

-

作曲家:Anonymous

-

作品集:Anonymous

-

作曲家:J. de Porta

-

作品集:J. de Porta

-

作曲家:Guillaume de Machaut

-

作品集:Machaut

-

作曲家:Paolo da Firenze

-

作品集:Paolo da Firenze

-

作曲家:Anonymous

-

作品集:Anonymous

-

作曲家:Guillaume de Machaut

-

作品集:Machaut

-

作曲家:Anonymous

-

作品集:Anonymous

-

作曲家:Jacob de Senleches

-

作品集:Jacob de Senleches

-

作曲家:Guillaume de Machaut

-

作品集:Machaut

-

作曲家:Guillaume Dufay

-

作品集:Dufay

-

作曲家:Gilet Velut

-

作品集:Velut

-

作曲家:Johannes de Lymburgia

-

作品集:Johannes de Lymburgia

简介

THERE IS A FAMOUS BOOK which interprets the fourteenth century as the time when the Middle Ages finally went to seed like the crops in Autumn. Another describes it as ‘the calamitous fourteenth century’. Small wonder, therefore, if the music composed in France during the century of Guillaume de Machaut (d1377) has often been described as ‘mannerist’ and ‘precious’: terms that suggest decadence and escapism. The performances recorded here spring from a different view of French music during the fourteenth century, for we believe that French song of the later Ars Nova can be described by a term that is both positive and evocative: Romantic. To be sure, these songs have been called Romantic before, but it may still seem rash to speak of ‘The Medieval Romantics’. Devotees of nineteenth-century music will object that there was no cult of genius in the fourteenth century, no passion for the wildness of Nature and no such nationalism as we associate with the 1800s. And yet if Romanticism implies a taste for beauty touched by strangeness, and if it is associated with a desire to expand the resources of musical language (and especially of harmony) with sheer profligacy of invention, then the second half of the fourteenth century in France was truly a period of Romantic composition. This is not to say that every composer of the period was a Romantic artist. Most of the polyphonic songs produced in France between c1340 and c1400 are light and melodious, being neither ‘wayward’ (a term often used of this repertory) nor Romantic. The virelai Mais qu’il vous viengne a plaisance bm is a representative example of this style at its best. Nonetheless, in addition to these plainer songs we find others, many of them attributed to named composers, which reveal different priorities. With the Romanticism of the fourteenth century—as with that of the nineteenth—a major priority is the sheer scale of what is attempted. To hear a thirteenth-century motet such as Quant voi le douz tans / En Mai / [Immo]LATUS 4, followed immediately by the four-part motet Alma polis religio / Axe poli / Tenor / Contratenor5of the next century, is to sense that there has been a great expansion in the musical territory colonized for composition. The later work is longer, its harmonic language more studied but also more diversified, and its compass much wider (reaching two octaves, the limit of the human voice according to contemporary theorists). With its complex isorhythmic scheme, it is altogether a more grandiose and intellectually ambitious work than its thirteenth-century counterpart. In the chanson repertoire of rondeaux, virelais and ballades, where the Romanticism of the later Ars Nova is principally to be found, the desire for expansive musical conceptions was closely allied (as it was to be five hundred years later) to an enlarged conception of melody. As early as the twelfth century, of course, some monophonic songs of the trouvères (not to mention some Latin songs) had been supplied with expansive, melismatic melodies, but the desire to stretch a long, measured melody over a large polyphonic frame was new in the fourteenth century. Among French composers of the Ars Nova this produced compositions going far beyond what could be accomplished in a thirteenth-century piece such as the motet just mentioned, Quant voi le douz tans / En Mai / [Immo]LATUS. In that piece, as it is performed on this recording, we hear first a monophonic song with its roots in the trouvère tradition, and then the same song as it was given mensural rhythm and placed above a vocalized tenor to make a motet, perhaps around 1240. As far as we can discern—for the origins of the polyphonic chanson in the fourteenth century are still obscure—this is one of the textures which passed to the fourteenth century and which helped to form the basis of chansons such as Guillaume de Machaut’s Tant doucement me sens emprisonnes 9, here performed as a duet comprising the Cantus and (vocalized) Tenor to display the mastery of Machaut’s two-part technique. The comparison with the thirteenth-century motet shows that the musical scope of Machaut’s piece is much greater than the Triplum–Tenor duet of the motet, largely because Machaut’s Cantus is so vast and needs so little support from the text. The thirteenth-century composer works syllable by syllable, but Machaut’s melismatic melody is directed, in particular, by a rhythmic elasticity which is entirely new to the fourteenth century and which merits comparison with some of the freedoms that were also ‘new’ in the nineteenth. We hear this freedom again in the highly flexible melodic line of the anonymous virelai Je languis d’amere mort 2, or in the Cantus of Paolo da Firenze’s Sofrir m’estuet et plus non puis durer7. Paolo’s piece demonstrates that the supposedly wayward rhythms of fourteenth-century song can be lyrical, even lilting, in their effect upon the ear, however strange they may look to the eye. In a similar way, the phrase-lengths in the Cantus of Quiconques veut d’amors joïr1, a superb piece by an anonymous master, are so supple that they resist ‘the tyranny of the bar line’ at every turn. There were many experiments with harmony among the medieval Romantics. As we leave the thirteenth century and enter the fourteenth century we become more confident that unusual harmonic effects may be tokens of a colouristic interest in harmony rather than the by-products of a compositional method. That kind of interest in harmony could coexist with the cerebral and calculating tendencies of all medieval composing, and indeed it could be advanced by them. The composer of Alma polis religio / Axe poli / Tenor / Contratenor 5, for example, is fascinated by a chord of B–G–D–G, and he exploits his isorhythmic scheme in such a way that the top three notes sound alone—so that the ear processes a simple chord of G—and then the low B flat enters in the Contratenor to tint the sonority in a most unexpected way. Many other examples could be cited from the pieces recorded here, but the master in this art is Solage, a composer who has left only ten securely attributed works, all of them experimental in various ways, and a high proportion of them in four parts (relatively rare in the chanson repertoire of the Ars Nova). His virelai Joieux de cuer en seumellant estoye 3, in four parts, is perhaps the summit of fourteenth-century Romanticism. The Cantus—the only part bearing the text—is a vast melody both in terms of its length and its width; it regularly spans a tenth or an eleventh within a few measures, a distance acknowledged by fourteenth-century theorists such as Jacques de Liège to represent the workable (if not the absolute) limit of the human voice. The other three parts are highly vocal in character, or in contemporary terminology, dicibilis (literally ‘pronouncable’). It is the essence of Solage’s achievement in this piece that the textless parts seem to strain towards the beauty and sufficiency of Cantus-style melody. What signs are there that medieval composers recognized that the later fourteenth century had produced composers of profligate inventiveness—musicians who had lent a touch of strangeness to beauty? The surest indication that composers of the fifteenth century recognized that something very striking had happened in the recent past is to be found in the kinds of pieces that they chose to produce themselves. The highly controlled scale and harmonic language of chansons such as Dufay’s Je requier a tous amoureux bp, the same composer’s Las, que feray ? Ne que je devenray ? bq or Gilet Velut’s Je voel servir plus c’onques mais br, are characteristic of much early fifteenth-century secular music and may be interpreted as a reaction against the luxuriance of later fourteenth-century composers such as Solage. When we turn to a mature composition of the mid-1430s, Johannes de Lymburgia’s Tota pulcra es, amica mea bs, we find a four-part technique completely unlike that of Solage. Lymburgia’s harmony is rigorously controlled so that almost every vertical sonority is a consonance, thirds and sixths are crucial building blocks of the music and fleeting rests are inserted in the texture to avoid dissonant colours that the ‘Medieval Romantics’ would have prized. PERFORMANCE The performances recorded here are based upon two principal assumptions. These are: (1) that the textless lines in fourteenth-century polyphony should not, save in exceptional circumstances, be texted, but should rather be vocalized or (less frequently, perhaps) performed upon instruments; and (2) that the partial texting increasingly found in the sources after c1400 should often be respected in performance and regarded as evidence for a cappella performance. Thus, in Johannes de Lymburgia’s Tota pulcra es, amica mea bs, the partial texting in the Tenor and Contratenor (at the words ‘Veni, veni’, for example) is preserved here; the singers momentarily abandon their vocalization to sing the underlay and then return to vocalizing. Since this recording was made these assumptions have been further strengthened by new research. This recording embodies the results of our experiments with vocalization. Using this technique one must find a vowel sound that keeps the textless parts bright but which does not overwhelm the changing vowel sounds of the texted part(s). For French music of the later Middle Ages the vowel in the Middle (and Modern) French tu seems ideal. It is strong in high harmonics and therefore bright. It is not tiring to produce over long periods (in contrast to the vowel in British English cool, for example). The first, second and third formants of the vowel in tu are relatively widely spaced and therefore it is not an inherently loud vowel (in contrast to the stem vowel in British English father, for example), and for the same reasons it is not inherently dark. It therefore exerts the minimum masking effect upon the changing vowels of the texted voice while retaining the brightness that is central to the aesthetic effect of this repertory. CHRISTOPHER PAGE © 1991