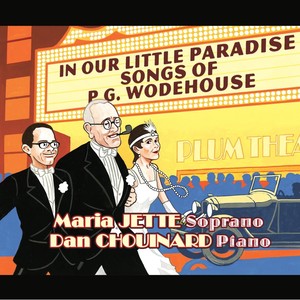

In Our Little Paradise: Songs of P.G. Wodehouse

- 流派:Easy Listening 轻音乐

- 语种:英语

- 发行时间:2011-10-22

- 类型:录音室专辑

- 歌曲

- 时长

简介

Have you ever wondered what P.G. Wodehouse was up to before cheerfully banging out 90+ novels about Jeeves & Wooster, various Mulliners, swine husbandry and savage aunts? Well, he spent a few years on Broadway in the early Jazz Age, re-jiggering the American musical with composers like Louis A. Hirsch, Jean Schwartz, and most famously, Jerome Kern, with whom he and librettist Guy Bolton created the epoch-making "Princess Theatre Musicals." The toughest thing about a mountain of material like Wodehouse’s lyrics is deciding what to leave out, because we’d really like to do it all! A glance at our song list reveals a lot that is not Kern-- we decided that Jerome Kern can take care of himself quite nicely. Instead, we’ve taken a chronological stroll through Plum’s theatrical career, from his very first professional outing in 1904’s Sergeant Brue until almost the end of it, 1928’s Rosalie, unscientifically selecting the lyrics and melodies we liked best from the un-Kerns. Most of these composers were big stars then, but are little known today. Technology is erasing that oblivion for many of them, though-- more and more of the pre-1922 songs are appearing online, ready to spring to life on your piano and in future recordings of the lyrics of P.G. Wodehouse! Maria Jette & Dan Chouinard October 2011 Minneapolis, Minnesota ABOUT THE SONGS: Wodehouse’s first contribution to the musical stage was a single number in Sergeant Brue, supplied at the request of its writer, the popular singer, comedian and playwright Owen Davis. Frederick Rosse (1867-1940) supplied the music to Put Me In My Little Cell, the first of several Wodehouse lyrics for “crooks.” Producer Frank Curzon had commissioned the composer Liza Lehmann (1862-1918), of In a Persian Garden fame (not to mention There Are Fairies at the Bottom of My Garden) to write the score. Unaccustomed to (and irked by) the common practice of interpolation in musical theater of the day, she never wrote another musical! The success of that single song led to a lyric-writing job at the Aldwych Theatre. The Beauty of Bath was also the germ of a historic partnership: the young American composer was a fellow named Jerome Kern (1885-1945). The plot involved Sir Timothy Bun and his twelve adopted daughters, the ‘Bath Buns’; the daughter of a viscount who falls for an unsuitable fellow (and actor!), and a handsome young Naval Lieutenant who switches identities with the actor. Kern & Wodehouse had their first show-stopping success in TBoB: a topical song about Joseph Chamberlain and an irksome tariff policy. The Frolic of a Breeze (sung by an otherwise unmentioned character named Tattersall Spink) lists both Wodehouse and F. Clifford Harris as lyricists. Wodehouse teamed up with an old newspaper colleague, Charles H. Bovill, and composer Frank Tours, to concoct a revue, Nuts & Wine. Poring over Barry Day’s fascinating and exhaustive The Complete Lyrics of P. G. Wodehouse, a lyric caught my Minnesotan eye: Two to Tooting. Thinking it sounded an awful lot like a vaudeville number, Two to Duluth (from Gideon’s The Heart Breakers: Princess Theater, Chicago, May 30, 1911), an old favorite here in Minnesota, I pulled out my copy. Sure enough, the composer was Melville Gideon (1884-1933), an American ragtime composer who’d supplied several additional numbers to N&W. With me, it was the work of a moment to deduce that Duluth had been sacrificed to Tooting, and we believe this recording marks the first outing of Two to Tooting since 1914. 1914 brought Plum back to the New York City he’d so enjoyed on a short jaunt ten years before. He married the future Lady Ethel, introduced several enduring characters and themes (Jeeves & Bertie Wooster, Blandings Castle) via magazines such as the Saturday Evening Post and Vanity Fair. In his capacity as theater critic for the latter, he ran into his old Beauty of Bath colleague, Jerry Kern, at his Very Good, Eddie, a new musical with a great book by Guy Bolton, but lyrics which were considerably less impressive. Kern’s happy experience with lyricist Plum led to a meeting of the three, and the American musical theater would soon take an evolutionary leap. George S. Kaufman’s verse in the New Yorker (variously attributed to Dorothy Parker, Lorenz Hart, and “anonymous”) reads: This is the trio of musical fame, Bolton and Wodehouse and Kern. Better than anyone else you can name, Bolton and Wodehouse and Kern. Nobody knows what on earth they’ve been bitten by, All I can say is I mean to get lit an’ buy Orchestra seats for the next one that’s written by Bolton and Wodehouse and Kern. The “Princess shows” were revolutionary in a musical theater world dominated by big, glamorous productions of operettas which still hearkened back to Europe’s operatic tradition, with large orchestras in the pit, large choruses on the large stages of large theaters, and big-name, expensive singers portraying aristocrats in fantastically expensive costumes and sets. The Princess, with its tiny, 299 seat house (300 would have meant abiding by a pricier fire code), went the other direction: a pit which held eleven players at the most, a stage which couldn’t hold more than a few chorus girls and boys, and most importantly, story lines which featured shopgirls and young businessmen, suburban lovers and comical small-time crooks, all of whom could be outfitted with regular modern clothing. It was musical comedy about the people in the seats. Oh, Boy! was the first of the famous string of hits for the new team. In the Kern “songbook,” Till the Clouds Roll By and Nesting Time in Flatbush are still sung today. Be a Little Sunbeam was cut during the tryout in upstate New York, but made our cut as an underdog Kern number! The next Princess Theater hit for the trio was Leave it to Jane, an adaptation of George Ade’s play, The College Widow. The plot revolves around the football teams of (Lutheran) Atwater College and (Baptist) Bingham College; a football star from a Big Ten school, whose scheming father, a Bingham alum, wants to sneak him onto the Bingham team; a couple of characters named Stub and Bub; a bevy of beautiful “college girls”; the spicy waitress, Flora; and Jane, the “it” girl on campus. Jack Ellsworth of WLIM in Patchogue, NY, recalls his 1970 interview with Wodehouse: “I asked Mr. Wodehouse, "Of all the songs you wrote with Kern, which were your favorites?" He replied, "Well, I'm very fond of The Siren’s Song from Leave it to Jane...” That beautiful number is the leading lady’s, of course; but it’s Flora who gets the real show-stopper, Cleopatterer. To Bolton and Plum, re-joining Hungarian operetta composer Emmerich Kalman (1882-1953) for The Riviera Girl, a re-working of Kalman’s Die Csárdásfürstin (The Gypsy Princess), seemed like a fine idea-- their previous collaboration, Miss Springtime, had been a hit. Unfortunately, RG was a flop. The complex plot involving a Hungarian actress, aristocrats in disguise and a marriage of convenience was confusing, and notwithstanding a Kern interpolation (the utterly un-Hungarian Let's Build a Little Bungalow in Quogue), apparently not funny enough to a Broadway audience-- no surprise, as its original, romantic and serious plot wasn’t amenable to farce-ification! Kalman (or Kálmán Imre, as he’s still known in Hungary) was Léhar’s equal in the “Silver Age” of Viennese operetta, and his original operetta (probably his biggest success) is beloved to the present day in Eastern Europe. The glorious Hungarian Emlékszel még? became Will You Forget?, and our miniature version substitutes a café accordion for the operetta’s cello. Jean Schwartz (1878-1956), another Hungarian by birth, was a New Yorker from the age of 11, and destined for Tin Pan Alley rather than operetta. A popular and prolific Broadway composer, his Rockabye Your Baby with a Dixie Melody and Hello, Central, Give Me No Man’s Land have lived on; but he was not Jerome Kern, and See You Later!, a Kern-less outing for Plum and Guy, never made it to Broadway, Princess-perfect though its outlines may have been. (Lee Davis relates the sad tale of its futile gestation in his Bolton and Wodehouse and Kern.) Nevertheless, most of the songs appeared in sheet music format, and we present three: The Train That Leaves for Town, a recurring species of Wodehouse lyric in which city folk display their naiveté about country living (a theme begun with Ukridge’s first appearance, 1911’s Love Among the Chickens); I Never Knew, an elegant romantic stroll; and Our Little Paradise, whose lyric is jam-packed with not only some delicious Wodehousian rhymes, but some of the earliest appearances of the abbrevs. which would be the bread and b. of Bertie and his fellow Drones. The last of the six “Princess shows” was Oh, My Dear! Jerry Kern, stung by Princess producer Ray Comstock’s rejection of The Little Thing, couldn’t be induced to sign on to another. Comstock snagged one of the hotter Broadway commodities: Kern’s childhood next-door neighbor, Louis A. Hirsch (1887-1924), whose Hullo, Ragtime had played 451 performances on London’s West End five years earlier, making him the most popular American composer in England. Back in New York, he’d more recently collaborated with George M. Cohan to great effect (1917’s hugely profitable Going Up), and was the indispensable composer of Flo Ziegfeld’s Follies. The Princess’s 299 seats meant a big financial sacrifice to a composer paid in a percentage of profits-- Hirsch’s usual venues were at least 1700 seats-- but the chic little Princess had a undeniable cachet for even a composer at the top of his Broadway game. The show’s timeline was awfully short, though, and the Toronto try-out opening in September 1918 under the original title, Ask Dad, featured several numbers by other composers (including Schwartz’s The Train That Leaves for Town, retitled Country Life), and surprisingly, Jerry Kern’s Go, Little Boat from Miss 1917. By the time Ask Dad had been massaged and pummeled into its November Broadway opening as Oh, My Dear!, Hirsch’s Go, Little Boat has replaced Kern’s placeholder, with a similar but re-worked lyric by plum, and a completely different, dreamy, Hirsch-y melody. Plum apparently felt that they didn’t quite click (he called it “our Ruddigore,” a reference to Gilbert & Sullivan’s least successful show). Hirsch researcher and champion Rick Benjamin points out that it couldn’t have been easy for Plum, accustomed to devising lyrics for a pre-written melody (a method which Kern enjoyed), to work with a composer who was accustomed to the more standard practice of writing music to fit a lyric-- and vice versa for Louis Hirsch. In her review, Dorothy Parker, who’d succeeded Plum as the Vanity Fair theater critic a few months earlier, was so dismissive of Hirsch’s music as to imply some kind of personal animus: “His music is so reminiscent that the score rather resembles a medley of last season’s popular songs, but it doesn’t make any difference-- Mr. Wodehouse’s lyrics would make anything go.” Countless subsequent writers, dutifully quoting her snappy remarks, have passed along and amplified the impression that some unworthy hack’s lousy music killed the show. Nobody who’d heard Our City of Dreams could say that! And a show that runs for 189 performances, then tours for a year and a half, isn’t exactly a classic failure. Lou Hirsch returned to his successes on the non-Princess side of Broadway. He turned out six more hit shows and revues, until a sudden bout of pneumonia killed him six years later. Dead at only 41, he was the most famous and prolific Broadway composer you’ve never heard of. Had he lived and composed for another twenty years, we might all know and admire his musical legacy as much as that of his childhood pal, Jerome Kern. Kissing Time was a re-tooled version (for the London audience) of The Girl Behind the Gun (New Amsterdam Theatre, New York; September 16, 1918), a profitable collaboration between Plum, Guy and Ivan Caryll (1861-1921). Born in Belgium, Félix Marie Henri Tilkin, a handsome, extravagant, dapper charmer, had not only the lifelong stage-name of Ivan Caryll, but a deliciously descriptive nickname: “Fabulous Felix”! His lengthy and elastic career began with a boost from Saint-Saëns in Paris. In London, he wrote operettas, songs and salon music, and had a long string of successful musicals at the Gaiety (including 1907’s The Girls of Gottenberg, to which Plum contributed a lyric) and elsewhere. At one point, he had five shows running at once in the West End. He came across to Broadway in 1911, where he incorporated the new ragtime-influenced styles and promptly turned out The Pink Lady (1911), the first of over a dozen hits. The Girl Behind the Gun was the sort of transformation Caryll had mastered over 25 years: converting a French play (in this case, a farce) into an English language musical (in this case, a wartime, patriotic one). Well-received in New York, it was hugely popular in London, where the post-war audience gobbled up the Anglicized version to the tune of 430 performances and an estimated one million viewers. There was almost a Fledermaus feel to the plot, with its disguises, mistaken identities, flirtatious husbands, vengeful wives, and appropriate reconciliations at the happy end. That Ticking Taxi’s Waiting at the Door was merely a title in the libretto in the U.S. version, but the song made it into the score of Kissing Time. Back in New York, all things Oriental were the rage, and the titillating play (involving sexual slavery!) East is West was a hot ticket. Willing to cash in on the trend, Plum and Guy signed on to The Rose of China, along with Armand Vecsey (1970-1949), a Hungarian immigrant who’d begun his musical career as a strolling restaurant violinist, and had risen to chef d’orchestre at The Ritz. He ended up with several Broadway scores to his credit, including 1927’s The Nightingale-- with Guy and Plum. Neither a spectacular set nor a gigantic orchestra (35 players, as opposed to the Princess Theatre’s typical band of eleven) could make up for an unpleasant story about Westerners in China who run against an ancient caste system, and Chinese characters who affect dense yet random “dialect,” even in song. In their hilarious (and only mildly accurate) theatrical memoir, Bring On the Girls, Plum wrote: “The advice that should be given to all aspiring young authors is: have nothing to do with a title like The Rose of China or The Willow Plate or The Siren of Shanghai or Me Velly Solly... in fact, avoid Chinese plays altogether. Much misery may thus be averted.” It does seem that most of the blame for The Rose of China’s failure may be ascribed to Bolton’s book, but even Plum had a few lyrics which made my skin crawl. Amid the muck, though, is the adorable and catchy Yale, a paean to his alma mater, sung early in the first act by Lee, a Chinese alumnus. A hint of Puccinian perfume seems to waft through it-- Madama Butterfly had its New York premiere in 1906. Plum took a shortish trip back to England in 1921, to work with one longstanding friend and colleague, George Grossmith, and one new one. Ivor Novello (1893-1951) was a golden boy: already a popular and successful composer of songs (Keep the Home Fires Burning) and operetta-flavored musicals, a publicity photo caught a film director’s eye in 1920, and his handsome face landed him a lead in a silent film. Stardom followed, and film work led to stage roles, and he was thoroughly adored by the British public. His four 1930s musicals were probably his best work, and he was easily the most popular British theater composer between Purcell and Britten. Just before the acting took off, though, he collaborated with Plum and Fred Thompson on The Golden Moth (subtitled, A Musical Play of Adventure). The title is the name of a café, which is the very busy scene for meetings of all sorts of characters in disguise: young French aristocrats worried about their arranged marriage, a notorious criminal and his sidekick, a policeman and a maid, and of course, a lot of pretty girls and “Apache” dancers. Aline de Crillon sings of her Fairy Prince; her Despina-ish maid, Rose, tortures her admirers with a sort of 1920s “catalogue aria,” Nuts in May; and, in a duet with Rose (If I Ever Lost You), the criminal’s sidekick, “The Marquis” (sort of a Leporello by way of Bertie Wooster), prepares to abandon the glamorous world of crime in favor of love. The Duncan Sisters were a couple of twenty minute eggs by the time they talked Irving Berlin into writing Sitting Pretty for them in 1922. Offspring of an L.A. violinist, they first took the stage at 14 and 16, and eventually took their unique mixture of close harmony and comedy to vaudeville stages and night clubs in New York and London. Plum and Guy signed on to the juicy-looking project, which was scheduled to open in the fall of ’23. Meanwhile, as Plum wrote to his friend Bill Townend: “...the Duncans asked Sam Harris, our manager, if they could fill in during the summer with a little thing called Topsy and Eva-- a sort of comic Uncle Tom’s Cabin which they had written themselves....and darned if Topsy and Eva didn’t turn out to be one of those colossal hits that run forever. It’s now in about its fifteenth week in Chicago with New York still to come, so we lost the Duncans and owing to losing them lost Irving Berlin, who liked Sitting Pretty but thought it wouldn’t go without them. So we got hold of Jerry [Kern] and carried on with him.” But what experienced producer would cast lanky brunette Gertrude Bryan and petite blonde Queenie Smith as the Duncans’ replacements, in a show whose plot revolved around twins? The reviews were decent, but the show never really caught fire. Still, it’s loaded with great lyrics, including a nostalgic “jail” number, Tulip Time in Sing-Sing, in the familiar mold of Put Me in My Little Cell. It’s hard to imagine cutting a title song, but Sitting Pretty was the victim of singer Dwight Frye’s speech impediment, which lent an unintended meaning to the phrase, “sit and sit and sit.” “We open the Bolton-McGuire-Ira Gershwin-Wodehouse-George Gershwin-Romberg show in Boston next week. It’s called Rosalie, and I don’t like it much...” wrote Plum to his old pal Bill T., in November 1927. It was a Ziegfeld show, and the original composer and lyricist had been fired, and Sigmund Romberg (1887-1951) Plum and the Gershwins brought in. It opened a couple of months later with Marilyn Miller as leading lady, and was perfectly successful. The film rights were bought by MGM, and Plum ultimately engaged to go to Hollywood and write it... but the saga of his $100K year of thumb-twiddling under-utilization in the film industry is such a well-known Wodehouse story that I need not repeat it here. (If the reader needs to refresh herself on the details, David Jasen relates it most delectably in P.G. Wodehouse: A Portrait of a Master.) We close our musical Wodehouse Walk with Romberg’s wistful waltz, Why Must We Always Be Dreaming?