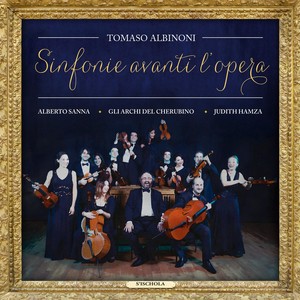

Tomaso Albinoni: Sinfonie Avanti L'opera

- 流派:Classical 古典

- 语种:英语

- 发行时间:2016-12-31

- 唱片公司:S'ischola

- 类型:录音室专辑

- 歌曲

- 时长

-

Symphony in F Major, Si 2

-

Symphony in A Major, Si 3

-

Symphony in A Major, Si 3a

-

Symphony in D Major, Si 4

-

Symphony in A Major, Si 5

-

Symphony in B-Flat Major, Si 6

-

Symphony in G Minor, Si 7

-

Symphony in G Major, Si 8

-

Symphony in F Major, Si 9

简介

A s'ischola production for EMAE (Early Music as Education) sponsored by FORA. Recorded (L’Aquila, Italy, 28-31 August 2015) and produced by Ian Percy. Photograph by Dan Kenyon. Graphic design by Francesco Dessi. Liner notes by Michael Talbot. The Latin word ‘symphonia’ and its equivalents in other languages have been used to define or describe a bewildering variety of musical compositions, from the Sacrae symphoniae of Giovanni Gabrieli at the end of the sixteenth century to the Chamber Symphony of Arnold Schoenberg. There is no common thread uniting all individual compositions so labelled, but there is a tendency for them to be instrumental rather than vocal, scored for ensembles rather than for single instruments and serious in character, often divided into several movements. The largest group is formed by concert symphonies for full orchestra dating from the Classical period onwards, but the next-largest group is probably that of the so-called sinfonie avanti l’opera (‘symphonies before the opera’), the overtures in three, occasionally two, movements that were used as curtain-raisers for Italian operas of all kinds from the late seventeenth century to the late eighteenth century (at which point single-movement overtures became preferred). One important function of an operatic overture was as a ‘noise-killer’. Opera houses in Italian cities were boisterous, unruly places where it was essential to give a strong signal to the audience to settle down and observe a modicum of silence before the singing commenced. This is the reason why all early eighteenth-century sinfonie begin with a firm, loud gesture – a custom that has to some extent survived up to the present day. A more artistically motivated function was to prefigure and encapsulate the range of moods that characterized the opera itself – hardly ever through direct allusion to its musical themes (this would have made it impossible to recycle favourite sinfonias from work to work, as composers liked to do), but instead through reference to the basic affetti (stylized moods) that provided the standard ingredients for baroque opera. The first movement, always the longest, emphasized the heroic, occasionally martial, aspect, which was sometimes interspersed with contrasting lyrical movements. The ensuing slow movement emphasized pathos or sweetness – the essence of the opera’s indispensable love-interest. The usually short finale was the purely instrumental analogue of the customary chorus or ensemble closing the opera in celebration of the mandatory happy ending. Because of this customary link to the happy ending, which resolved all tensions and redeemed all the vicissitudes that had occurred en route to it, the vast majority of operatic sinfonias were written in major keys. Visitors to the opera in Italy liked to travel home with a souvenir of what they had heard, and to this end visited the copying shops (copisterie) that had prepared the musical material for the production, where they made their orders. Sometimes, they purchased the complete opera, but more often, they purchased only extracts. These could include the sinfonia, which, one imagines, were often intended for domestic performance as recreational music, since most were written for an ensemble of two violins, viola, string bass (cello and/or double bass) and continuo, and therefore, if no doubling instruments were available, could be performed by as few as five players. Similarly, sinfonias could appear as free-standing items in public concerts. Already by the third decade of the eighteenth century sinfonias modelled on the operatic prototype were being purpose-written for concert use – and these were, of course, the ancestors of the modern concert symphony from Sammartini onwards. Many, indeed most, of the Italian sinfonias acquired by collectors and today preserved in libraries all over Europe do not identify the particular opera (assuming that there was one!) to which the work in question was originally prefaced. Having no text, they cannot be matched to any libretto. De facto, therefore, they have become concert works not unlike the contemporary concertos for strings without soloist (so-called ‘ripieno’ concertos), but always preserving the distinctive physiognomy of their genre. The eight sinfonie a quattro for strings by Tomaso Albinoni (1671–1751) featured in the present recording are classic cases in point. With one exception, they are preserved independently of operatic scores and give no hint in their title (or any annotations made to it) of any individual opera or operas to which they were once attached. These concise, attractive compositions both exemplify the common features of the genre in the first four decades of the eighteenth century and the highly individual musical style of their composer. Only one of them can be precisely dated, but the clear pattern of evolution exhibited by Albinoni’s musical language enables reliable approximate dates to be given. Albinoni was one of the most successful amateur composers of his time. His family, which manufactured playing cards, had acquired a degree of wealth through a lucky inheritance, a fact that enabled him to pursue his main interest: music. He was a capable singer and violinist, and without ever experiencing the need to ‘go professional’ and enter the service of some patron, augmented his private income by working from home in Venice as a highly active teacher and composer. He is today best known as a composer of sonatas and concertos who was both an inspirer and later a musical beneficiary of his slightly younger and more famous fellow Venetian, Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741). But he was concurrently a prolific composer of secular vocal music (over 80 operas, numerous serenatas and over 50 chamber cantatas) who between 1700 and 1725 ranked as one of the leading figures in that domain in Venice and, indeed, Italy. The opening sinfonia on this recording, identified as Si 2 in the present author’s catalogue of Albinoni’s works, is the earliest of the sinfonias. (The catalogue appears in Michael Talbot, Tomaso Albinoni: The Venetian Composer and his World (Oxford, 1990).) Si 2 survives in the Austrian National Library in Vienna, but is also found at the head of the score of Engelberta, a five-act opera composed jointly by Albinoni (who wrote the overture and Acts I–III) and the older composer Francesco Gasparini (1661–1727) to close the 1709 carnival season at the Venetian theatre of San Cassiano. A copy of the opera score is held by the Vienna library and also by the Deutsche Staatsbibliothek PK in Berlin, where, in an annotation, the division of labour between the two composers is described. (Such collaborations, sometimes unacknowledged publicly, were very frequent at the time, a common reason being extreme pressure of time.) Although this sinfonia is in some respects simpler than most of those that followed it, all the essential Albinonian ingredients are in place, especially the delicious quasi-conversational interchanges between the violin parts. (To satisfy curiosity: Si 1 is the sinfonia to Albinoni’s earliest opera, Zenobia, regina de’ Palmireni (Venice, 1694). It includes an obbligato trumpet part and an extra viola part, and for this purely practical reason is omitted from our selection.) Si 3, Si 4 and Si 5, preserved in manuscripts in Vienna and Stockholm, are similar enough to appear contemporary, dating to 1710 or shortly after. An interesting variant of Si 3, labelled Si 3a, was published without Albinoni’s name as the third work (‘Sonata III’) in an anthology brought out by the Amsterdam publisher Estienne Roger around 1709–12 under the title VI Sonates ou Concerts à 4, 5 & 6 Parties. The publication was dedicated by Roger to (and financed by?) Leon d’Urbino, a Jewish banker resident in Amsterdam who was an amateur musician and apparently hosted a music club (collegium musicum) there. Si 3a could well have been specially ordered by d’Urbino from the composer. It is a work clearly intended for recreational use, as shown by its attractive fugal finale, fugue being a speciality of Albinoni, as we know from his Op. 5 and Op. 9 concertos. Its first movement and, less exactly, its second movement are paraphrases of their counterparts in Si 3. Albinoni disguises the first-movement paraphrase by altering its frequently repeated motto (or head-motive), although the intervening passage-work and the cadences that follow survive intact. Such semi-concealed recycling, practised also by Vivaldi, is typical for the age. The slow movement is ‘fused’ to the opening movement, becoming, as it were, its coda. This is a fairly common solution in sinfonias of the time: in extreme cases, as in Vivaldi’s sinfonia entitled L’improvisata, the slow movement can be suppressed altogether. Si 3 and Si 4 are similar enough not to need separate description. It must be conceded that to a certain extent Albinoni was formulaic in his approach to musical composition in all genres. He played to his strengths and repeated processes that had earned him approval earlier. But one could say much the same thing about the Corelli trio sonatas or Haydn symphonies. Si 4 at any rate must predate 1714, since it was used as the overture to a pasticcio (multi-authored) opera entitled Creso (Crœsus) given at the Haymarket theatre in London in that year. Some ten years later, Si 4 was published in London by John Walsh without the composer’s name in a collection of sinfonias (Six Overtures for Violins in all their Parts). Si 5 is perhaps as close to an ‘archetypical’ Albinoni sinfonia as one can get, displaying most of the features already commented on. It opts for the ‘slow movement as coda’ formula, achieving an effective surprise through the sudden turn from A major to B minor marked by the rise of the bass from A to A sharp. Si 6 and Si 7 belong to the world of the late 1710s, the period when Albinoni was most strongly influenced by the music of Vivaldi (as we note especially in his Concerti a cinque, Op. 7, of 1715). They survive only in Dresden, where they may well have been brought by the musicians of the Saxon court who came with the electoral prince in 1716 to Venice, where they remained for almost a year. Of the pair, Si 6 is the more conventional in mood. Vivaldian influence is evident in the first movement, with its well-judged balance between thematically prominent motives, here enlivened with syncopation, and passe-partout passage-work in semiquavers, utilizing both broken-chord and scalic figures, without which no Albinoni fast movement is complete. The slow movement, featuring ‘jagged’ rhythms, is the familiar short succession of chords offering some tonal contrast. The binary finale is unpretentious but elegant, giving the second violin, which often crosses over the first, some brief moments of glory. The passionate storminess of the opening movement of Si 7 is not unexpected for an operatic sinfonia, but its minor tonality certainly is. Perhaps the piece was composed not for an opera but for a dramatic cantata (serenata) or for concert use. The first movement features some highly effective interchange of musical figures (in quavers and semiquavers, respectively) between the two violin parts, which almost seem locked in a quarrel. The slow movement exhibits the tender melancholy typical of such movements and reveals Albinoni’s great gifts as a melodist capable of spinning out a shapely cantilena over many bars. Once again, the composer selects binary form for the finale, which, so to speak, combines the energy of the first movement with the elegance of the second. Si 8 and Si 9 are identifiable from their style as products of the 1730s, not far from the end of the composer’s active career. By this time, a group of composers trained in the Neapolitan conservatories (Porpora, Leo, Vinci) and their imitators all over Italy had revolutionized the common musical language, introducing what we today term the galant style, characterized by a rhythmically complex and highly nuanced melodic line supported by simple, functional harmony. Older composers such as Albinoni and Vivaldi could not but adapt their style in accordance with the new fashion, although elements of their earlier compositional methods remain. In Albinoni’s case, the violins speak the new language, the viola and bass the old, and the formal structures remain exactly the same as they were thirty years earlier. Si 8 survives in Uppsala and Stockholm. Its energetic and strepitoso opening movement illustrates three typical features of sinfonia style: the use of unison writing to produce a ‘muscular’ effect; rasping multiple-stopped chords in the violin parts for a similar purpose; the occasional silencing of the bass during lyrical interludes (and in preparation for the invigorating impact of the bass’s re-entry). In this sinfonia the slow movement, a harmonically unsettled succession of chords similar to that in Si 9, is also ‘fused’ to the opening movement. Albinoni’s captivating finale, dance-like and in 3/8 metre, is cast in binary form. In Si 9, preserved only in the university library of Lund in Sweden, recognizable elements of Albinoni’s familiar musical language are the complex ‘intertwining’ of the two violin parts (in instances where they do not go in unison), the steady tread of the bass, the fast rate of chord-change and the generally diatonic musical language – a feature that makes chromaticism even more potent whenever it momentarily surfaces. The brief slow movement, a succession of somewhat unpredictably modulating chords, is a mere separator between the fast outer movements. The finale is typically Albinonian in its ebullience. Arthur Hutchings, the author of a pioneering book in the baroque concerto (1961), was right to observe: ‘[Albinoni] was [...] one of the few musicians in all history who could produce long and entirely gay movements as admirable as other men’s serious movements’. Within the spectrum of musical creation running from the routinely produced to the individually crafted, Albinoni’s sinfonias mostly gravitate towards the first category. But in this composer’s hands the ‘routine’ is rarely other than pleasing. The reason partly lies in his forthright and individualistic style and partly in the many subtle touches of which the listener often becomes aware only after repeated hearings. The great nineteenth-century historian of music in Venice Francesco Caffi identified nerbo (sinewy strength) as a prime characteristic of Albinoni’s operatic music, and this quality certainly informs his sinfonias. (All nine sinfonie a quattro in the present recording are published individually in full score and separate parts by Ut Orpheus Edizioni, Bologna, in a critical edition by Fabrizio Ammetto.)