- 歌曲

- 时长

Disc1

Disc2

简介

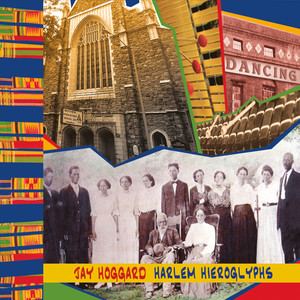

Jay Hoggard’s new album, Harlem Hieroglyphs, represents both the culmination of all his previous work as well as a new direction. The paradox fits seamlessly into his life—and to all that is jazz, he explains.The personnel on the recording is GARY BARTZ soprano and alto saxophones, JAMES WEIDMAN piano.organ NAT ADDERLEY JR piano,organ BELDEN BULLOCK bass and YORON ISRAEL drums. At his 40th Reunion concert on April 30, he will give a concert based on this album, reprising one that he’ll have given on campus just a few weeks prior to that. And on April 15&16, the piece that is his collaboration with Associate Professor of Dance Nicole Stanton and Professor of English Lois Brown, titled Storied Placess, will be performed. It will be the professors’ culmination of a year-long Collaborative Cluster of courses grouped under that title. The new compositional direction that fascinates Hoggard is toward an implicit narrative thread, such as that framed in the word “migrations.” This is the concept with which he created Harlem Hieroglyphs, a two-CD set begun when he was on sabbatical last year that takes a listener through a “a spectrum of jazz—standards from musical theater to an extended form they call ‘rhythmic’ jazz.” The personnel on the recording is GARY BARTZ soprano and alto saxophones, JAMES WEIDMAN piano.organ NAT ADDERLEY JR piano,organ BELDEN BULLOCK bass and YORON ISRAEL drums. “All the jazz greats—Duke Ellington,Fletcher Henderson,James P Johnson,Earl Hines, Lionel Hampton,Dizzy Gillespie, John Coltrane,Miles Davis, they’ve all left their sonic hieroglyphs in the music we now play,” he says. “Every composition on this record is an exploration of how I have come to think the way I do and what has brought me to hear music from the angle that I do.” And while students in the Collaborative Cluster may have dealt with the concept of migration in general terms, Hoggard was thinking about the specific one that brought his family from a farm in North Carolina—where his great-grandfather was born into slavery in the first half of the 19th century—to New York City. Both will offer a concert hall venue—“People are tired of going to hear jazz in a basement venue half the size of this practice room,” he says. “They’re ready for something different.” He acknowledges that the fluidity of improvisational jazz will have to bend slightly to allow dancers to inhabit the music in a way that allows the dancers to know what to expect and coordinate their movement to the music As for the creation of collaborative art. “It is mystical and it’s something that—you just can’t explain. People ask me, ‘How did you both know to end there?’ It’s the communicative experience. And that’s been part of the experience of working with dancers. I’ve asked, ‘How did y’all know how to do that together?’ Well, they just know. What I call improvisation is spontaneous composition. It’s extemporization in the context of a compositional format. Any musical moment has these multiple layers—melody, harmony and rhythm—and so you are manifesting in the middle of that, melodically and rhythmically, and reacting to the harmonic structure. That’s where the genius is in jazz. It’s like 10-dimensional chess: there’s melody, harmony and rhythm identifiable parts, but then there’s all the rest—and it’s mystical.” Photo caption of the covers of his cd: The photographs on the CD cover tell his migration story in collage: “That’s Wright Cherry, my paternal great-grandfather, and there’s my grandmother with her siblings on their farm in North Carolina. There’s the Mother AME Zion Church, where I spend a lot of time as a child. That’s the Renaissance Ballroom—the place you’d go to hear music—but it’s now torn down. In 2016, it’s nothing to travel from North Carolina to New York City—but in the early days of jazz? That was a journey, a real migration.” ---Cynthia Rockwell, associate editor WESLEYAN Magazine