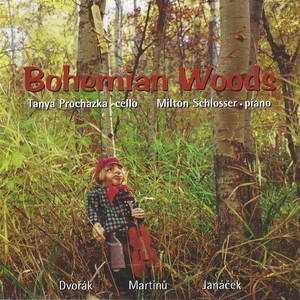

Bohemian Woods

- 流派:Classical 古典

- 语种:英语

- 发行时间:2004-04-06

- 类型:录音室专辑

- 歌曲

- 时长

-

Pohadka (Fairy Tale)

-

Sonata No. 2 for Cello and Piano, H. 286

简介

To a large extent, nationalism flourished most prominently in countries outside the principal musical centres of Europe. Nationalism flourished in Scandinavia, for example, more so than Italy; it flourished in Spain more strongly than France (though most of Spain's composers received formal musical education in Paris before heading home). What need had France, or Italy or Germany to specifically espouse its idiomatic music? Those centres were magnets for music of all kinds. In the case of the Czech people embracing the regions of Moravia, Slovakia, and Bohemia - the situation is a little different. Some of the strongest strains of nationalism in music came from Czechoslovakia. Yet compared to other centres, that region, and its major city Prague in particular, already had a fairly significant music base. Prague, after all, was where Mozart's Le nozze di Figaro had its first resounding success in 1787 - nearly one hundred years before nationalism, as an identifiable musical force, swept through Europe and beyond. Some outstanding musicians (one thinks of the Stamitz family of violinists, or Krumpholtz or Dussek) and even composers (Zelenka, Vanhal, Myslivecek) had come from Bohemia, Krommer (like Janacek) hailed from Moravia. A solid tradition of art music composition dated as far back as the 16th century, when Hapsburg Emperor Rudolf II chose to rule from Prague (rather than Vienna), and so set up a court there, complete with a musical establishment. By the time Bedrich Smetana (1824-1884), father of Bohemian nationalism, arrived on the scene, there was certainly a measurable influence of Czech music in Europe. But whereas Smetana's aim was to establish a repertory of Czech music for the Czech people, those in the next generation or two sought more actively to spread their nationalism outward, beyond Bohemia. The most famous composer to do so was Antonin Dvorak (1841-1904), who had no less a champion for his music than Johannes Brahms. After a glowing recommendation for Dvorak written by Brahms to his publisher Simrock, the young Czech submitted a set of Moravian Duets to the German music publisher. Sufficiently impressed, Simrock immediately pressed Dvorak for a commercially viable set - something like the very popular Hungarian Dances that Brahms had turned into bestselling stuff. Three months later in 1878, Dvorak presented Simrock with his first set of Slavonic Dances, scored originally for piano duet, and very much the success for which Simrock and Dvorak could have hoped. As popular as the set proved to be, there was more gold to be mined from this vein, and Dvorak in short order had not only produced an orchestral version of the eight dances of his Dp.46 set, but had also arranged some of them for different instrument combinations. Two of the dances were written for cello and piano. Like nearly all of Dvorak's works for cello (including the concerto), the two Slavonic Dances, as well as the adaptation of Klid, were written for his friend and fellow staff member at the Prague Conservatory, Hanus Wihan. For the cello dances, the ordering of the pair has the eighth dance of Op.46 followed by the third. Dance no. 8, in G minor, is a furiant, a dance in 3/4 time idiosyncratically "Bohemian-sounding" enough that Dvorak used it often, especially in the scherzos of his symphonies. Dance no. 3 is a polka, originally in A-flat, though written a step up for cello and piano. As fresh and inventive as many of Dvorak's works are, there are also some that were written entirely to please the amateur, and of course Simrock. The piano duet cycle From the Bohemian Forest, published as his Op.68, is a pleasant set of musical pictures of the countryside. Dvorak didn't even think of the titles for the individual movements of the six-picture set until after he had composed them. He even joked that the titles were hard to come up with because Schumann had used all the best ones. But if the set does not represent Dvorak at his most inspired, the lovely melody of the fifth piece, Klid, made a charming piece for cello and piano when Dvorak toured briefly with Wihan in 1891. It has become known in English as Silent Woods, and Dvorak would later orchestrate it. Pohadka translates as "fairy tale", though the tale that serves as the inspiration for Leos Janacek's most famous work for cello is fairly incidental to the piece. Cast in three sections Pohadka dates from 1910, by which time Janacek had finally attained a measure of respect and admiration - something that had been a long time in coming. Comparisons between Janacek and Dvorak were inevitable, with the Moravian only 13 years younger than the more famous Dvorak. Janacek can be thought of as being to Dvorak what Mussorgsky was to Tchaikovsky; his music is earthier, the folk music of Czechoslovakia in its raw state, with less melodic refinement, perhaps. Like Bartok had done in Hungary and Vaughan Williams in the U.K., Janacek collected and anthologized the folk music of his homeland. Language was particularly important to him, and as he got older, he became more obsessed with how speech rhythms and patterns should inform his music. "All of the melodic and rhythmic mysteries of music can be explained in reference to the melody and rhythm of the musical motives of spoken language", he once said. There is less of this in Pohadka, however - as Janacek explores the full range of the cello's palette, with pizzicato both delicate and sharply struck, and a lush, fluidly melodic line, infused in the final section with a gentle dance. The piano often supports the cello's line with ostinato patterns, though there are strong melodies given to it as well. Based on the manuscripts, it is believed that the Presto for Cello and Piano not only dates from the same time as Pohodka, but is thought to have been a sketch for the second movement of Pohadka. It was revised subsequent to its composition in 1910, and first performed on 15 June 1948 by Karel Krofta (cello) and Zdenka Prusova (piano). It has become something of a "party piece," with its brief, breezy nature making it an attractive encore. Taken all together, the cello works written by Bohuslav Martinu (1890-1959) could fairly stand as the most significant contributions to the instrument of the 20th century. He wrote four works for cello with orchestra, three sonatas, and several other pieces. While there is a strong element of his Czech homeland, and its dance rhythms and harmonic understanding, in his music, Martina spent most of his life away from Czechoslovakia. He left for the first time in 1923 to go to Paris, and the notion of returning was made impossible when the Nazis took over the country. He left for the United States, and when the Communists overran Czechoslovakia after World War Two, Martina was left a permanent exile. Martinu's Czech influences were constantly imbued with other strong influences; the jazz he heard in Paris, for example, or his thorough understanding and appreciation of baroque counterpoint is another example. His upbringing and his constantly fragile health meant that his formal musical education was piecemeal, and the result was a highly individual style but one which mayor may not follow the contemporary compositional styles. He followed his own path, and while the modern styles and techniques he heard around him might find their way into his compositions, Martinu was never slavishly bound by contemporary vogue. Musicality was always a first consideration. Nevertheless, Martinu turned to his native land in the final year of his life for the Variations on a Slovakian Theme. Several years before this, Martinu, constantly in fairly fragile health, had sustained severe injuries to his head after a fall, and his output after that varied as did his ability to concentrate or even remember things. The five variations that make up this work, based on a song called Keby ja vedela ("Had I known") show him in a period of lucid clarity, with as strong a grasp of how to manipulate a melodic line as ever. The theme is introduced in F minor, with the variations tending to alternate between major and minor keys although each variation also brings in rhythmic and tonal variations as well. The first variation is in moderate tempo, with a strong role for the piano serving as the introduction to the second variation. Its cello line becomes resigned, though still noble, a mood which carries into the third variation as well. The final variation, a vibrant Allegro in a happy E Major, is a witty and virtuosic dialogue. Martinu's Second Cello Sonata dates from the year he came to the U.S. (1941), and just after the successful premiere of one of his most famous pieces, the Concerto grosso. It was soon after arriving in New York that Martinu met cellist Frank Rybka, another musician of Czech heritage. It was to him that Martinu dedicated the sonata, though it was premiered by Lucien Laporte (with Elly Bontempo) on March 27,1942. A harmonic link from Martinu's opera Julietta features prominently in the opening Allegro. The middle slow movement leans heavily on the cello's expressive potential, while the concluding movement is a technically demanding one for both cellist and pianist. There is also a cadenza for the cello toward the end of the final movement - linking it spiritually to a concerto. Both cello and piano, however, are matched inextricably throughout the work, a feat Martinu achieves with ingenious balance and refinement.