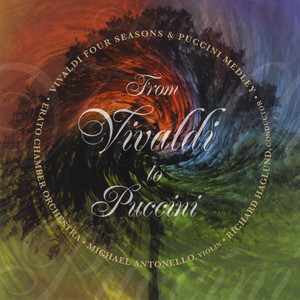

From Vivaldi to Puccini

- 歌唱: Richard Haglund/ Michael Antonello/ Peter Arnstein

- 乐团: Erato Chamber Orchestra

- 发行时间:2013-11-01

- 类型:录音室专辑

- 歌曲

- 时长

-

作曲家:Antonio Vivaldi

-

作品集:Concerto No. 1 in E Major, La Primavera (Spring), RV 269

-

作品集:Concerto No. 2 in G Minor, L'estate (Summer), RV 315

-

作品集:Concerto No. 3 in F Major, L'autonno (Autumn), RV 293

-

作曲家:Antonio Vivaldi

-

作品集:Concerto No. 4 in F Minor, L'inverno (Winter), RV 297

-

作曲家:Giacomo Puccini( 贾科莫·普契尼)

-

作品集:La bohème, Gianni Schicchi

-

作曲家:Johann Sebastian Bach( 约翰·塞巴斯蒂安·巴赫)

-

作品集:Partita No. 2, BWV 1004

简介

Antonio Vivaldi was known as il prete rosso, the redheaded priest. He practiced in Venice at Ospedale della Pietà, an orphanage for girls that included a music program that would put Interlochen to shame. Many of the girls came from rich families who didn’t want them, so much of the funding for the school may have been guilt money. Vivaldi was employed by the Pietà off and on all his life, and always had the opportunity to experiment there and perform his concertos. Vivaldi presided over mass every day, but it soon became obvious to the authorities that his heart wasn’t in it. He lost his curacy when, as his biographer, Wasielewski notes: “Once, while reading daily mass, he was overcome by the urge to compose. He interrupted his priestly functions and went into the sacristy to discharge his musical thoughts and then returned to end the ceremony. Of course, the matter immediately created a stir and Vivaldi was brought before the church authorities for disciplinary action. The body in question was lenient and decided to relieve him of the duty of celebrating mass in the future, since it appeared that he was not quite right in the head.” Like every composer before and since Vivaldi, the height of one’s success was proven by achievement in the field of opera. Vivaldi composed 94 operas and became a director and impresario for a theater near Venice. But his early experience at the Pietà, for which he was required to compose, brought him success only in concertos, especially those for the violin. Most of his operas are lost and his efforts there came to naught. However, his instinct for setting scenes, for sudden changes of mood and extremes of emotion, which should have made him a great opera composer but somehow failed, seeped into his concertos and brought them to life. He was an opera composer for the violin. In Vivaldi’s time, the concerto was a new form of music, much in vogue, and Vivaldi became its leader. In the opera performances he led, both his own and others’ operas, he performed on the violin between the acts. In reviews of these operas, disappointment was expressed if Vivaldi did not perform. His musical personality as a solo violinist was one that “frightened” or “terrified” his listeners, and, of course, thrilled them, as Uffenbach, a contemporary reviewer often noted. In this sense, he developed an artistic reputation similar to the violinist Paganini, a century later, whose success was fueled by his reputation of being possessed by the devil. In his published violin concertos, Vivaldi stayed within certain defined technical limits, rarely venturing beyond fourth position—no point in publishing something too difficult for anyone but him to play. But accounts of his unpublished cadenzas show how much further he could go. As Uffenbach writes in his diary: “Toward the end Vivaldi played a splendid solo accompaniment to which he appended a fantasy [cadenza] that gave me a start because no one has ever played anything like it, for his fingers were within a straw’s breath of the bridge, so that there was no room for the bow. He played a fugue on all four strings at unbelievable speed, astonishing everyone…” Vivaldi may have viewed opera as a means to make money, but he must have been thoroughly frustrated by his inability to make the kind of exciting artistic innovations that he so easily brought to his concertos, a field in which he was universally acknowledged as the leading composer. His operas contain much of the same kinds of music as his concertos; as in the storm scenes from The Seasons, Vivaldi wrote rampaging scales and arpeggios for the voice in his “storm” opera arias, which failed either because such writing is ineffective for the voice (reviews mention “hammer-blow rhythms” and rapid scales), or because he overshadowed the voice by the virtuosity of the orchestral violin parts. Reviews of his choral works often accused him of being a concerto composer; however, this typecasting was sometimes based on false assumptions—the vocal writing in his inimitable Gloria is glorious. Operatic ideas are common in The Seasons. Taking from the opening of the Winter concerto, he reused the music which he described as “frozen trembling in icy storms” in an aria meant to show the “flowing of blood.” Opus 8 is a group of pieces, headed by The Seasons. These four violin concertos include sonetto dimstrativo, sonnets presented before each movement, probably by Vivaldi himself. Vivaldi further marked in the music the exact points where particular lines of the sonnet imagery pertain. Only the solo violinist is aware of these imaginative, poetic instructions. Were these verbal cues placed there to inspire the violinist? Were they added as a marketing tool, to help sell the music, which was in instense competition with many other composers’ concertos, as well as his own? Was this his way of showing his artistic commitment to the music, much as Stradivarius and other elite violinmakers did, who added double purfling (a fine necklace pattern of ingrained wood) to their violins, a decoration having no effect on the superb quality of the instrument’s sound? Did his sonnets force his patrons to stand up and take more notice of The Seasons, which he worked on and polished for years; did the sonnets make them stand out far and above his other violin concertos? (Vivaldi wrote approximately 440 concertos, half of them for violin, at a steady rate of two per month.) If so, it was a stunning success, both during his lifetime and after. It is strange that Vivaldi would go into such detail with these programmatic, poetic descriptions, when these four violin concertos are his tightest and most well-constructed compositions, music that is more than able to stand on its own. In general, the fast movements have multiple images and moods to express (as described in the sonnets), the slow movements only one. Perhaps the verbal images helped inspire him to a heightened sense of drama. Sonnets from The Seasons Spring Spring has returned and with it gaiety Is expressed by the birds in joyous song, And the fountains, caressed by young zephyrs, Murmur sweetly as they flow. As the sky is clouded all in black, Lightning flashes and thunder roars; But after they die down, the little birds Return to sing their enchanting song. While on the flowering meadow, Among the murmuring of leaves and boughs, Dozes the goatherd, watched over by his faithful dog. To the pastoral bagpipes’ festive sounds Dance loving nymphs and shepherds, in love, Under brilliant springtime skies. Summer Under the heat of the burning sun Man droops, his herd wilts, the pine is parched The cuckoo finds its voice, and singing with it, The dove and the goldfinch. Zephyr breathes gently but, countered, The north wind appears nearby and suddenly The shepherd cries because, uncertain, He fears the wind squall and its effects. His tired limbs get no rest, unnerved by His fear of lightning and wild thunder, While gnats and flies in furious swarms surround him. Alas, his fears prove all too grounded— Thunder and lightning split the heavens, and hail Slices the tops off corn and grain. Autumn The peasants celebrate with dance and song The joy of a successful harvest. With Bacchus’s liquor liberally drunk, Their festivity ends in slumber. They leave behind the song and dance To seek the pleasant mild air. The season invites more and more To savor the joy of sweet sleep. The hunters leave for the hunt at dawn With horns and guns and hounds they go; The quarry flees, but they pursue. Bewildered and exhausted by the great noise of guns and hounds, the wounded prey Nearly escapes, but is caught and dies. Winter Frozen and shivering amid the chilly snow Our breathing hampered by the horrid wind As we run, we continually stamp our feet Our teeth chattering with the awful cold; We move to the fire and contented peace While the rain outside comes down in sheets. We walk on the ice with slow steps Careful how we walk, for fear of falling; If we move too fast, we slip and fall to the ground Again treading heavily on the ice Until the ice breaks up and dissolves. We hear from behind closed doors Boreal winds and all the winds of war. This is winter, but one that brings joy. Puccini What do you do if you want to be an opera star but both your talent and your professional opportunities lie with the violin? If you’re Vivaldi, you’re out of luck, other than performing violin concertos between the acts. But if you’re a violinist born more than two centuries later, you can indulge yourself to your heart’s content by immersing yourself in Puccini, bringing back to the violin Vivaldi’s unrealized dreams, after two hundred years of growth in the world of opera. All of Antonello’s favorite melodies from La Bohème and Gianni Schicci are presented here. Notes by Peter Arnstein [Peter Arnstein bio] Dr. Arnstein is well known in the Twin Cities area as a pianist and composer. He has often served as pianist and harpsichordist with the Minnesota Orchestra, and has accompanied and recorded with many members of the Twin Cities’ two main orchestras and college music faculties. He has performed numerous times at the Edinburgh Festival in Scotland, as both piano soloist and harpsichord soloist, as accompanist for violinist Michael Antonello, and as part of the piano trio, Trio di Vita, which premiered his Trio Jazzico Nostalgico and Scottish Fantasy. Dr. Arnstein’s compositions include more than 100 chamber music works, hundreds of piano solos and duets, songs in English and in French, and music for orchestra and chorus. His music has been published in both the United States and Europe. He also serves as the Twin Cities' Classical Music Examiner for examiner.com.