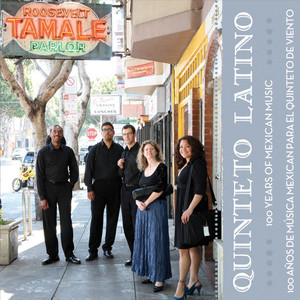

100 Years of Mexican Music for Wind Quintet

- 流派:Latin 拉丁

- 语种:英语

- 发行时间:2012-01-16

- 类型:录音室专辑

- 歌曲

- 时长

简介

CD Booklet notes - English - Spanish Son de la Bruja (2007) and Tenue (2007) by JOSÉ LUIS HURTADO (1975- ) Son de la Bruja is Hurtado’s personal—and witty—version of “La bruja” (“The Witch”), one of the most popular Mexican folk tunes performed as a son jarocho (from the coastal region of Veracruz). Originally a musical genre accompanied by dance, the son jarocho results from a rich afro-mestizo influence. Its structure is based on an alternation of verses and refrains (binary form), and presents an invitation for improvisation, both in text and music. Unusual for its slow tempo, this triple-meter son presents a wavy melodic contour; the theme rises and falls, invoking the imagery of flying at night, as suggested by the folk tune’s opening line: “How wonderful it is to fly at two in the morning!” Following a brief introduction, the clarinet presents this theme in its “original form.” Hurtado plays with the suggestive nature of the lyrics by presenting a series of variations on the theme: it is doubled, fragmented, combined with playful hemiolas, and using a hocket technique, where the melody is divided between two or three of the instruments. The last iteration of the refrain increases the tension by the use of trills of high range and brings this piece to a festive end. According to Hurtado, “tenue” refers to tranquility, calm, shadow, and sporadic thin rays of light. This work was commissioned by Armando Castellano to be performed by Quinteto Latino in 2007. The first movement opens with a rhythmic motive that is presented in imitative polyphony across the three upper voices in unison. Soon after the range is expanded and the imitation gives room to an independence of voices. While the first section of this movement presents a frequent alternation of meters, the middle section—of thinner texture—explores a wider range of the instruments. The melodic voices sustain tense sonorities, which are poignantly masked by the open register. The second movement starts in utmost tranquility with a unison across the voices. The register opens up in a conjunct fashion that leads to tense moments of sustained half-steps. Extended techniques, such as flutter tonguing and multiphonics, are used subtly to enhance timbral diversity. Towards the end of the movement the rhythmic motive that opened the piece is recalled, with the three upper voices presenting it in imitative fashion. While the oboe continues with the iteration of the repeated pitch, the other voices sustain an open and tense chord of extreme range, which brings the piece to a close. Soli No. 2 (1961), by CARLOS CHÁVEZ (1899-1978) The image of Carlos Chávez as a composer of “nationalist” pieces has clouded his role as an advocate for avant-garde music. Soli No. 2 is the second of four experimental works of the same title where the composer explored the principle of non-repetition. In his 1961 lecture at Harvard, Chávez stated that: “The idea of repetition and variation could be substituted for the notion of a constant rebirth, a true derivation: a stream that never returns to its source, an eternally flowing stream, like a spiral, always connected and continuing its original source, but always in search of new and unlimited spaces.” In this piece Chávez assigns a solo role to each instrument of the quintet, corresponding to the five movements. Hence, the flute acts as the soloist in the slow Preludio, the oboe in the cheerful Rondo, the bassoon in the lyrical Aria, the clarinet in the light Sonatina, and the horn in the emphatic Finale. The composer makes use of serial procedures, most clearly perceived in the twelve-tone theme introduced by the bassoon in the third movement. Soli No. 2 has a secure place in the repertory of the twentieth-century woodwind quintet for it is a brilliant example of atonal contrapuntal techniques. Danza de mediodÌa (1996), by ARTURO MÁRQUEZ (1950- ) Driven by a profound interest in Mexico’s bailes de salÛn, Arturo Márquez has since the 1990s written a series of works that allude to certain rhythmic and melodic patterns characteristic of this music. Danza del mediodÌa (“mid-day dance”) is a tribute to the composer’s fascination with the danzÛn, a musical genre of Afro-Cuban origin that has remained one of the most popular public couple dances in Mexico. In Márquez’s own words: “DanzÛnís apparent lightness is just a cover letter for music full of sensuality and qualitative rigor.” This sectional work starts with an introductory passage of layered texture; while the bassoon introduces a four-bar ostinato, the musical dialogue between the oboe and clarinet present rhythmic variety with the use of syncopation, triplets and cinquillos cubanos—characteristic of the danzÛn. Intended to be performed con fuoco (with passion), the main thematic material is first presented by the flute and followed by the clarinet. The liveliness of this section soon transitions into an expressive slower section, where a nostalgic melody is carried by the oboe and followed by the bassoon. While the main theme is previewed after an acceleration of tempo, an additional contrasting section is introduced, one where the horn and bassoon interchange thematic material in a more agitated texture. After a return of the lyrical theme of the slower section, the clarinet leads the piece into a final transition. The expected main theme comes back renewed, this time taking us into a festive and convincing conclusion. Cinco danzas breves by MARIO LAVISTA (1943- ) Cinco danzas breves (1994) is a collection of dances that testifies to the profound interest Mario Lavista has in medieval and Renaissance contrapuntal procedures, especially the use of canons, rhythmic and melodic repeated patterns, and the symbolic use of certain intervals. The composer considers these dances as divertimenti—lighthearted pieces to be performed in social functions. He says: “My divertimento is conceived in this spirit and it is destined for five imaginary choreographies.” The opening dance is based on a short theme and its counter-theme, both of which are exchanged by all the instruments of the quintet. Rhythmically challenging, this lively movement carries its dynamism until the final cadence. In the second dance the oboe introduces thematic material primarily based on the interval of a minor third. For the composer, the perfect fifth symbolizes the perfection of the creative logos, while the interval of the third, major or minor, represents the presence of men. The following dance creates contrast by presenting a playful and witty iteration of rhythmic motifs of short notes, which are juxtaposed with cantabile thematic lines interchanged by the five instruments. The fourth dance, introspective and whimsical, presents a subtle exploration of timbres by the use of different fingerings for repeated pitches. A gentle and slow theme is introduced in imitative counterpoint between oboe, clarinet and flute. After a faster and irregular middle section, there is a return to the slow texture of the beginning. The last movement, a fast and challenging dance, continues with the exploration of small rhythmic and melodic motifs, which travel among the five instrumental lines. An obsessive rhythmic pulse on a repeated pitch drives the piece to a quieter conclusion. Estrellita (1912, arr. 1995), by MANUEL M. PONCE (1882-1948) This wonderful and eclectic sonorous journey, which has included some of the most representative works for wind quintet written by Mexican composers, concludes on a sweet and wistful note with Adam Lesnick’s arrangement of Manuel M. Ponce’s Estrellita (“Little Star”). Without a doubt, this piece for voice and piano is Ponce’s best-known work. The lyricism and simplicity of this song transports us into a sense of nostalgia. The opening lines of the text, written by Ponce himself, say: “Little star from a distant sky, who sees my pain, who knows my suffering. Come down and tell me if she loves me a little, because I can no longer live without her love.” After a brief introduction, flute and oboe present the main melody in parallel harmony, while clarinet, horn and bassoon provide an austere accompaniment. The theme is stated a second time by clarinet and horn with a softer accompaniment by flute and bassoon. When the theme is presented a third time, the bassoon introduces a basic habanera rhythmic figure. A second theme follows, which soon leads to a last mention of the initial theme (da capo aria). Ponce once stated that, “Estrellita is living nostalgia; a complaint on behalf of a youth that is being lost. She embodies the cobblestoned streets of Aguascalientes and my dreams of walking by moonlight.” Notes by Ana R. Alonso-Minutti - Texas, May 2011 Son de la bruja (2007) y Tenue (2007) de JOSÉ LUIS HURTADO (1975- ) Son de la bruja es una versión personal—y muy ingeniosa—de “La bruja”, una de las melodías mexicanas más populares dentro del repertorio de sones jarochos (de la costa de Veracruz). Originalmente, un género musical acompañado por danza, el son jarocho resulta de una rica influencia afro-mestiza. Su estructura está basada en la alternación de versos y refranes (forma binaria) y presenta una invitación a la improvisación, tanto en texto como en música. Inusual por su tempo lento, este son de métrica triple presenta un contorno melódico ondulante; el tema sube y baja, invocando la imagen de un vuelo nocturno, sugerido por el verso inicial de la canción popular: “¡Ay qué bonito es volar a las dos de la mañana!” Después de una introducción breve, el clarinete introduce este tema en su “versión original”. Hurtado juega con la naturaleza sugestiva de la letra al presentar una serie de variaciones sobre el tema: es doblado, fragmentado, combinado con pícaras hemiolas, y usando hockets, donde la melodía es dividida entre dos o tres de los instrumentos. La última iteración del refrán incrementa la tensión por el uso de trinos de rango agudo, y concluye la pieza con un final festivo. Para Hurtado, “tenue” implica calma, tranquilidad, sombra, delgados rayos de luz esporádicos. Esta pieza fue comisionada por Armando Castellano para el Quinteto Latino en 2007. El primer movimiento abre con un motivo rítmico presentado en polifonía imitativa a través de las tres voces superiores en unísono. Poco después, hay una extensión en el rango y la imitación da lugar a una independencia de voces. La sección inicial del movimiento presenta cambios de métrica frecuentes; la media —de textura más delgada— explora un rango más amplio de los instrumentos. Las voces melódicas sostienen sonoridades tensas, disfrazadas quizá por la apertura de rango. El segundo movimiento comienza en completa tranquilidad con las voces en unísono. El registro se abre en un movimiento melódico conjunto que lleva a momentos tensos de semitonos. El uso de técnicas extendidas, como frullati (tremolo) y los multifónicos, son sutilmente usadas para realzar la diversidad tímbrica. Hacia el final del movimiento el motivo rítmico que abrió la obra se reincorpora en imitación por las tres voces superiores. Mientras el oboe continua con la iteración de la nota repetida, las otras voces sostienen un acorde abierto y tenso de rango extremo, con el cual se concluye la obra. Soli No. 2 (1961) de CARLOS CHÁVEZ (1899-1978) La imagen de Carlos Chávez como un compositor de obras “nacionalistas” ha nublado su rol como partidario de las corrientes de vanguardia. Soli No. 2 es la segunda de cuatro obras experimentales del mismo nombre, en las cuales el compositor exploró el principio de la no-repetición. En su ponencia en la Universidad de Harvard (1961) Chávez expresó: “La idea de repetición y variación puede ser sustituida por la noción de un constante renacer, de verdadera derivación: una corriente que nunca regresa a su fuente, una corriente en eterno desarrollo, como una espiral, siempre ligada a su fuente original y continuándola siempre, pero buscando sin descanso espacios nuevos e ilimitados”. En esta pieza Chávez asigna un rol solista a cada instrumento del quinteto, correspondiente a cinco movimientos. De esta manera, la flauta actúa como la solista en el lento Preludio, el oboe en el alegre Rondo, el fagot en la lírica Aria, el clarinete en la ligera Sonatina, y el corno en el enfático Finale. El compositor hace uso de procedimientos seriales, que se perciben más claramente en el tema dodecafónico introducido por el fagot en el tercer movimiento. Soli No. 2 tiene un lugar asegurado dentro del repertorio de obras para quinteto de aliento del siglo XX por ser un ejemplo brillante de técnicas contrapuntísticas atonales. Danza de mediodÌa (1996) de ARTURO MÁRQUEZ (1950- ) Llevado por un profundo interés en los bailes de salón mexicanos, desde principios de la década de 1990, Arturo Márquez ha escrito una serie de obras que aluden a ciertos patrones rítmicos y melódicos característicos de esa música. Danza del mediodÌa es un tributo a su fascinación por el danzón, género musical de origen afro-cubano que ha permanecido como uno de los bailes públicos más populares en México. En palabras del mismo Márquez: “La aparente ligereza del danzón es solo una carta de presentación para una música llena de sensualidad y rigor cualitativo que nuestros viejos mexicanos siguen viviendo con nostalgia y júbilo como escape hacia su mundo emocional”. Esta obra seccionada comienza con un pasaje introductorio con diversas capas en la textura; mientras el fagot introduce un ostinato (patrón repetido) de cuatro compases, el diálogo musical entre el oboe y clarinete presenta una variedad rítmica por el uso de síncopas, tresillos, y cinquillos cubanos, característicos del danzón. Siguiendo la indicación con fuoco (con pasión), el material temático principal se presenta primero por la flauta, seguido por el clarinete. La vitalidad de esta sección transita pronto hacia una pasaje más lento y de mayor expresividad, en el cual el oboe eleva una melodía nostálgica seguida por el fagot. Después de una aceleración del tempo, el tema principal se anuncia, seguido por una sección contrastante donde el corno y fagot intercambian material temático en una textura más agitada. El tema lírico de la segunda sección regresa y la línea del clarinete lleva a la obra a una transición final, donde el tema inicial vuelve renovado, esta vez llevándonos hacia una conclusión contundente y festiva. Cinco danzas breves (1994) de MARIO LAVISTA (1943- ) Cinco danzas breves (1994) es una colección de danzas que testifican sobre el profundo interés que Mario Lavista ha tenido en procedimientos contrapuntísticos del Medievo y Renacimiento, sobre todo en el uso de canones, repetición de patrones rítmico-melódicos, y el uso simbólico de ciertos intervalos. El compositor estas como divertimenti—piezas de carácter ligero para ser tocadas en ocasiones sociales. Sobre éstas, Lavista dice: “Mi divertimento está concebido en este espíritu y es destinado para cinco coreografías imaginarias”. La danza inicial está basada en un tema de tres compases y su contratema intercambiado por todos los instrumentos del quinteto. El dinamismo de este movimiento, el cual es rítmicamente demandante, es prolongado hasta la cadencia final. En la segunda danza el oboe introduce el material temático el cual está principalmente basado en el intervalo de la tercera menor. Para el compositor la quinta perfecta simboliza la perfección del logo creador, mientras que el intervalo de tercera, mayor o menor, representa la presencia del hombre. La siguiente danza contrasta con las anteriores al presentar, de manera ingeniosa y juguetona, la iteración de motivos rítmicos de notas cortas oscilantes que son yuxtapuestas con líneas temáticas marcadas cantabile que son intercambiadas por los cinco instrumentos. De carácter contemplativo, la cuarta danza presenta una exploración tímbrica obtenida por cambios de digitaciones en notas repetidas. Un tema lento y gentil se introduce en contrapunto imitativo entre el oboe, el clarinete y la flauta. Después de una sección media irregular y rápida, el movimiento concluye con un retorno a la textura lenta inicial. El último movimiento, una danza rápida y técnicamente demandante, continua con la exploración de pequeños motivos rítmicos y melódicos que viajan entre las cinco líneas instrumentales. Un pulso rítmico obsesivo de notas repetidas lleva la pieza hacia una conclusión serena. Estrellita (1912, arr. 1995) de MANUEL M. PONCE (1882-1948) Este maravilloso y ecléctico viaje sonoro, que ha incluido algunas de las obras más representativas para quinteto de alientos escritas por compositores mexicanos, concluye con Estrellita de Manuel M. Ponce (arreglo de Adam Lesnick). Sin duda alguna, esta pieza para voz y piano es la obra de Ponce más conocida. El lirismo y la simplicidad de esta canción nos transportan a un estado de nostalgia. Las líneas iniciales del texto, escrito por Ponce mismo, dicen: “Estrellita de lejano cielo, que miras mi dolor, que sabes mi sufrir. Baja y dime si me quiere un poco, porque ya no puedo, sin su amor vivir”. Después de una breve introducción, la flauta y el oboe presentan la melodía principal en armonía paralela, mientras que el clarinete, el corno y el fagot otorgan un acompañamiento austero. El tema se repite una segunda ocasión por el clarinete y el corno, con un acompañamiento más suave otorgado por la flauta y el fagot. Cuando el tema se presenta por tercera vez, el fagot introduce una figura rítmica característica de la danza habanera. A esto le sigue un segundo tema de corta duración, que pronto da lugar a una última mención del tema inicial. Sobre esta canción Ponce declaró: “Estrellita es una nostalgia viva; una queja por la juventud que comienza a perderse. Reuní en ella el rumor de las callejas empedradas de Aguascalientes, los sueños de mis pasos nocturnos a la luz de la luna”. Notas escritas y traducidas por Ana R. Alonso-Minutti - Texas, Mayo 2011