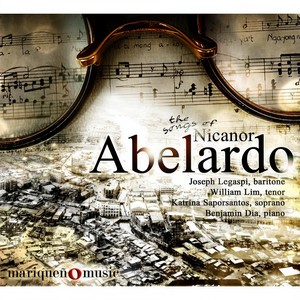

The Songs Of Nicanor Abelardo

- 流派:Classical 古典

- 语种:英语

- 发行时间:2013-03-30

- 类型:录音室专辑

- 歌曲

- 时长

简介

The contributions of Nicanor Sta. Ana Abelardo (1893-1934) to Philippine music history go beyond his prolific output spanning over 140 works. He was an innovator, a man of his times, whose efforts became instrumental in paving the way for the legacy of modern composition in his country. Music was definitely alive in the Philippines before the 1900s, but prior to this era, the music of the Filipinos thrived only within the people themselves. Only a handful of examples were put on paper the way music in the West had already been for a great part of history. Formalized musical composition did not become part of Philippine culture until the latter part of the nineteenth century. Pioneer composers in this period of infancy were barely able to catch up with the evolution of music in the Western world, yet they produced masterpieces that would herald the heritage of Filipino musicality. The early generation of composers, which included the likes of Marcelo Adonay, Rosalio Silos, and Julian Felipe, quickly rose to show how homegrown talents were more than capable in crafting works adhering to the rudiments of the Western common practice or classical music, as most would call this style. The generation that followed would then bring forward the development of Philippine composition by taking indigenous musical styles and transforming them into more structurally sophisticated art forms. Nicanor Abelardo belonged to this generation that updated Filipino music in a milieu of a Philippine society undergoing modernization. The weight of the contributions of Nicanor Abelardo to Philippine music goes beyond sheer quantity. Along with his compatriots, he took the next step in the evolution of Filipino composition by taking native idioms and molding them into more complex styles not unlike the way Schubert and his fellow masters borrowed elements from their native folk songs and cultivated them in Lieder. Most popular among the genres Abelardo helped develop was the kundiman, a folk song type originating from the cundiman, the local serenade of Tagalog-speaking people. From a simple tune recognizable through the sentiment of its words, the kundiman was elevated into specific compositional form first developed by colleague Francisco Santiago. Abelardo and Bonifacio Abdon, another contemporary, followed suit in further defining and proliferating the genre’s new incarnation as a sophisticated art song form. While there are many variations on the form, a kundiman can easily be identified by the following salient features: it has a triple time signature; it is in moderate speed (sometimes referred to as tempo de kundiman); its first half, which could be divided into two smaller sections, is in a minor key; and, its second half is in the parallel major. The contrast between minor and major tonalities flow in accord with the emotions of the text, which usually begins in a somber mood of a pleading wooer then turns into a hopeful yearning for the beloved’s response. What distinguishes Abelardo’s kundimans from that of his compatriots is the use of words that depict personas with lingering and unresolved despair. Compared to Santiago’s, which often portray a pursuer’s optimism, those of Abelardo are often wrought with melancholy from beginning to end. This turns the device of modulating from minor to major into an ironic intensification of pain, rather than the usual relief from tension. Perhaps this distinction is why Abelardo is hailed as one of the major kundiman composers, even though he only composed about ten. One can easily observe this hallmark in the examples included in this album. The well-known (4)Nasaan Ka, Irog? (Where Are You, Love?) features the heart-wrenching image of a broken vow caused by class differences — a story based on the real-life experience of Abelardo’s friend, Dr. Francisco Tecson, to whom the song is dedicated. Like many of the composer’s kundimans, this, as well as its Spanish version (5)¿Dónde estás, mi vida? begins and ends in yearning for the lost lover. This theme of constant longing for lost love is very common among Abelardo’s kundimans. (9)Magbalik Ka Hirang (Return to Me, Chosen One) reminisces a past love, with a vow to wait endlessly. (13)Nasaan ang Aking Puso (Where is My Heart?) tells of a love abruptly lost and a desperate plea for the lover’s return. (3)Pahimakas (Testament) is a tormented farewell to yet another missing lover. Such examples show the image of an abandoned feminine figure invoking an absent lover as she pledges her fidelity in an archetypal act of martyrdom, which traditional Filipino mores sanctifies. Abelardo, of course, did not avoid the quintessential image of a masculine figure serenading his beloved below her window or balcony. However, the masculine personas in his kundimans take a more lugubrious, instead of charming, approach to their courtship. For instance, his first documented kundiman, the iconic (1)Kung Hindi Man (If Not), shows the inconsolable dejection of a quasi-suicidal devoted lover —a romantically lauded image in Filipino melodrama. (10)Himutok! (Song of Distress) and (14)Sa ‘Yong Kandungan (On Your Lap) are yet two examples that morbidly describe the wooer’s pain as he pleads for relief from the pursued. Meanwhile, (6)Kundiman ng Luha (Love Song of Tears) depicts the suitor’s persistent yearning not only in the title, but more so in the persona’s overt emotional outpouring. This may be seen as intensely counter-culture, considering that Philippine society inherited Spanish machismo and would normally ridicule a man willing to shed tears out in the open. However, the use of such a scenario further exemplifies the persona’s ultimate devotion. Not all of Abelardo’s kundimans are drenched in gloom, however. One very notable exception to his somber-themed works is (7)Bituing Marikit (Beautiful Star), which is perhaps the most popular of Abelardo’s kundimans, if not the most popular kundiman in the entire repertoire. This one takes a lighter theme of a more typical serenade wherein the persona likens the beloved to a guiding star. What is different, however, is that unlike most of the noted examples, the words of this kundiman were neither written nor chosen by Abelardo himself, since it is part of Dakilang Punglo (Noble Bullet), a sarswela with libretto by Servando de los Angeles. Thus, the choice of doleful themes in all his other kundimans very well have been a deliberate one for Abelardo. The kundiman was not the only native idiom Abelardo explored and modernized. Another native song form that he adopted was the kumintang, a pantomime dance song that usually involves a male and a female perspective in a context of courtship. While this genre is not as widely composed as the kundiman, its foremost example, (8)Mutya ng Pasig (Pearl of Pasig), outshines many songs in the Filipino repertory. Abelardo saw the kumintang as the appropriate vehicle to pay homage to the bygone splendor of the Pasig River, an important geographical feature of Manila. The piece also involves two perspectives, but instead of a man courting a woman, the voices of a storyteller and a water nymph would be depicted. Interestingly, Abelardo also ingeniously molded the kumintang into the kundiman form. The song opens in a minor configuration patterned after a native chant known as tagulaylay, a declamatory style in which the narrator describes the nymph that once reigned in the river. The nymph’s perspective then comes forth in the parallel major with the more dance-like, pantomimic tune, worthy of a graceful water deity. Such complex use of different devices shows Abelardo’s mastery of his people’s music and his proficiency in compositional conventions from the West. Abelardo belonged to a unique generation that thrived at the cusp of the two major colonial eras in the Philippines, and so it is not surprising for him to take advantage of influences from Spain and America. Many of his songs have Spanish versions. He also utilized Hispanic elements in a great number of his compositions. In (11)Pahiwatig (Implication) and (12)Ikaw Rin (Still, You), he makes use of the habanera to set his own text teeming with his trademark doleful sentimentality. He was not alien to American culture, either. Having taken his graduate studies at the Chicago Musical College (now part of the Chicago College of Performing Arts at Roosevelt University), he was able to assimilate American elements into his style. In (2)Amorosa (Loving), he employs a foxtrot to set Jesus Balmori’s Spanish poem about a beautiful ballroom dancer. This melding of the language of the past colonizers with the popular music of his country’s new wardens makes a cunning representation of this transitional point in Philippine history. Some of Abelardo’s works show a good sense of awareness of the social issues that were happening around him. The novelty ditty (15)Naku... Kenkoy! (Oh Dear... Kenkoy!) employs a quasi-ragtime style to portray the popular character Francisco “Kenkoy” Harabas from the comic strip series by Romualdo Ramos. The witty and catchy flair of the song appropriately depicts colonial mentality —an affliction of many a Filipino who denies his own culture in pathetic attempts to be American or Westerner, only to be busted by his indelible native idiosyncrasies. Abelardo’s ability to wade through different musical, cultural, and linguistic waters is key to his immortality in Philippine music. He was able to shift from classical to popular styles with ease, while maintaining integrity and even championing tradition. Like his contemporaries in Europe and America, Abelardo composed and performed for a wide range of platforms, from dance halls to theaters and salons to concert stages. He lived right in time for Manila’s makeover as an entertainment center where opera, jazz, vaudeville, sarswela (the Filipino adaptation of the Spanish zarzuela), and many other genres would quickly find a home in a harmonious assembly that blurred the lines separating traditional and vernacular styles. It does not come as a surprise that shortly after his death, some of his songs were taken as thematic platforms for some of the most iconic films in the then budding Philippine movie industry. If not for his short life span, Abelardo’s creativity would probably had taken flight beyond the maturity of what his works had achieved, as evidenced in his post-1931 instrumental compositions such as the Panoramas Suite, which greatly resemble the avant-garde expressionism of the Second Viennese School, but with an undeniably Filipino flavor. He was a creator who knew how to take advantage of the richness of the materials available to him because of where and when he existed. Short-lived he may have been, Nicanor Abelardo lived in an opportune time and place to developing one’s craft, whether in commerce, architecture, politics, or music. The first quarter of the 20th century was a time of accelerated progress in the Philippines, as it moved from Spanish rule to revolution and independence, then to American occupation through the 1898 Treaty of Paris. The political control of the Americans came with a package of economic, social, infrastructural, and cultural upgrades that made colonial rule less onerous for the Filipinos. Within just a few decades in the early 1900s, the capital city Manila would metamorphose into a cosmopolitan gem rivaling cities of its better-known neighboring nations in this once obscure corner in the Far East. Hallmarks of a full-fledged modern metropolis would quickly rise, with architectural landmarks such as the National Museum, National Library, and Manila Hotel. Cutting-edge public transport would become available to Manileños with Asia’s first electric tram system, the sprawling Tranvia. Public health and education were accessed by citizens with the founding of institutions such as the Philippine General Hospital and the University of the Philippines. Perhaps this surge of growth around Abelardo was a catalyst to the development of his artistry. At present, 120 years after the birth of Nicanor Abelardo, the Philippines is once more experiencing another surge of development and progress. Amidst the instability of the global markets that originated with the recessions in the US and Europe, the small nation is being recognized by the world as a new soaring leader in economic growth. It is fitting to revisit a body of work created out of a time of a similarly remarkable advancement. Living in a period of stability was perhaps conducive to Abelardo’s creative juices as his output boasted over 140 works, despite his short life. As emerging Filipino musicians, we offer this album as a tribute to the master’s significant contribution to Philippine music and as a celebration of an age of blossoming for our homeland. After all, the efforts of pioneers such as Maestro Abelardo, within such a propitious landscape then and now, are instrumental to empowering upcoming musicians to carry on the heritage of Filipino artistry.